Four hundred years ago, our ancestors began importing native black Africans from their home continent to the North American continent, in chains, shoved below the decks of ships built especially for the purpose of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade.

Three hundred years ago the practice of chattel slavery was so well entrenched into British-Colonial North American culture, that it was not only legal, but widely practiced in every single British colony in this hemisphere. In the southern colonies of the eighteenth century, the number of African descent slaves vastly outnumbered the number of white colonists, creating a social dynamic infused with fear and terror. Slave owners and their white employees feared violent uprising. Using their power and money, acquired largely through the benefit of slave labor, they influenced the courts and colonial legislative bodies to begin passing ever-more draconian laws against those of African Descent – forcing those few individuals who had managed to purchase their own freedom or win manumission through other means to leave the place where they were born, raised, and earned their living – to leave their families and friends still in bondage, behind. To stay meant to be forced to return to slavery. It’s in this era that it became legal for an owner to beat, mutilate, or even kill his slaves “as he saw fit”.

Two hundred seventy-six years ago, the Stono Slave Rebellion began in the colony of Charleston, South Carolina. The rebellion failed and everyone involved was either executed or sold into the West Indies. In response to the rebellion, the South Carolina legislature passed the Negro Act of 1740 restricting slave assembly, education, and movement. It required legislative approval for manumissions, which slaveholders had previously been able to arrange privately.

Two hundred twenty-seven years ago, after the American Revolution was won by the former British colonies of continental North America, the Constitution of the United States of America was ratified. The preamble of this document reads, “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Within the same document, the founding fathers saw fit to enshrine chattel slavery as the law of the land, and to measure a person of African heritage as equal to 3/5 of a person.

Two hundred and twenty-four years ago, the Haitian Revolution began as a slave revolt in the French Colony of Saint-Domingue. This slave uprising was successful and culminated in the elimination of slavery there and the founding of the Republic of Haiti. The Haitian Revolution is generally considered the most successful slave rebellion ever to have occurred and it was a seminal moment in the histories of both Europe and the Americas. The success of the slaves on Saint-Domingue in throwing off the yolk of colonial rule through violent rebellion, the organized murder of plantation owners, and armed insurrection against a vastly superior military force, simply terrified white, slave-owning Americans. What occurred at Saint-Domingue caused a new round of extremely draconian legislative actions to be passed in the American South, as well as increasing militarization of the southern states.

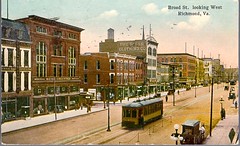

Two hundred and fifteen years ago, not far from Richmond Virginia, a slave named Gabriel Prosser launched a plot to execute plantation owners and slaveholders, and to seize the city of Richmond. He recruited more than fifty slaves at the outset of his plan, but was thwarted by a fellow-slave who communicated a warning to his master. The planned rebellion failed at the very last moment before it was to be carried out, but the fact that it was very nearly successful shook Virginian’s to their core. Everyone found to be associated with the plot was executed. The state of Virginia responded by raising county-wide, highly-trained, regularly drilled militias, and the city of Richmond became a militarized camp with armed militia members patrolling the city on foot and horseback and parading around the capitol grounds on a daily basis. The militarization of Virginia continued unabated until the end of the US Civil War.

Two hundred and eight years ago, the Parliament of Great Britain passed the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which outlawed the kidnapping, imprisonment, export, and sale of African slaves. The British Navy aggressively enforced this legislation, which through blockade, seizure of vessels, and prosecution of ship owners and crews, brought a halt to the lion’s share of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. The impact on the former colonies in North America was profound, shutting down the possibility that fresh slaves could be purchased to replace those worked to death (average lifespan after arrival to North America was five years) in the brutal sugar, rice, and indigo industries of the Deep South and Caribbean regions. Shortly after the implementation of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, American plantation owners in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina – particularly in central and eastern areas of those states where the farm land had been depleted – began purposeful and increasingly more sophisticated slave breeding programs based on contemporary cattle, horse, and pig breeding methodologies.

Between 1830 and 1860, roughly 10,000 slaves per month were sold or traded from the bustling slave market at Shockoe Bottom in Richmond, Virginia. This number was eclipsed by the larger, older, and even busier market at New Orleans, and it was nearly matched by the competing slave markets at Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia. Taking just the Virginia numbers into account, more than three million individual slaves were bred, raised, and sold out of the piney woods of Virginia into the sugar, rice, and indigo killing fields of the Deep South.

Slavery – not plant agriculture (tobacco, cotton, grains) – was Virginia’s largest and most profitable industry in the decades leading up the US Civil War. Slavery made the state of Virginia the wealthiest in the United States, at a time when the United States was already competing with Great Britain to become the wealthiest nation in the world.

One hundred and fifty-four years ago the United State Civil War began. People, even today, argue as to what the cause of the war was, but few rational people will deny that the central points of debate had everything to do with money and political power. In 1860, the South possessed great wealth and great political power. The North and the emerging west felt that the South’s dominance was due to the constitutionally enshrined 3/5’s rule, which gave the South a disproportionally larger representation in the United States House of Representatives – and due to the reality that Southern employers did not have to pay wages to their workforce, a situation which gave them an unfair competitive advantage compared to employers in non-slave states.

When the United States government passed the Conscription Act, forcing millions of mostly young, recently immigrated, poor young men into service in the United States Army and Navy in support of the Union government in the Civil War, violent riots erupted, most notably in New York City. The city spiraled into chaos, with most of the animas directed at the city’s African population. An orphanage was attacked and looted, numerous homes and business were looted and burned, thousands of African American New Yorkers were assaulted on the streets, in their places of work, and in their homes. 120 African-descent New Yorkers were murdered over the three day riots before the US Army occupied the streets and forcibly restored order. This event remains the largest civil and racial insurrection in American history, aside from the American Civil War itself.

As the Civil War ramped up, the Southern Slave Trade continued. Despite The Emancipation Proclamation of January, 1863, nearly all American’s of African descent remained in bondage. Many of those who found themselves near the Union Army, chose to “run” hoping for freedom. What they found instead was forced labor under dreadful and dangerous circumstances, neglect to the point of starvation, constant marching with little or no housing provided to protect them from the elements, and being labeled “contraband” by the leaders and soldiers to whom they had fled seeking safety and relief.

For those that remained behind southern lines, nothing changed. Families were broken up. People were traded like cattle. There was no hope for freedom. It could not be bought, stolen, or earned. In the American South during the Civil War, it became illegal to free one’s slaves, or to transport them out of the reach of the Confederate government. As the deprivations of war took hold – food shortages, lack of fuel, lack of shoes and material for clothing – it was the slaves who endured the worst of the famine, cold, and nakedness. The slaves, who had always gotten the scraps left unwanted by their masters, got little to nothing at all.

When the Civil War ended with a Union victory in 1865, all the slaves in America were made free. Since it had been illegal for a slave to own private or even personal property, the overwhelming number of former slaves had absolutely nothing with which to begin their new lives. Never-the-less, many managed to quickly pull themselves up and start small businesses, lease farms abandoned by economically devastated former plantation owners, even build schools and begin to educate themselves and become politically active in an effort to improve their status in society and improve their lives and hopefully the lives of their children.

During the “Reconstruction” period after the conclusion of the Civil War, Union soldiers occupied much of the defeated south, and through their armed presence, enforced a nascent form of early civil rights. The South’s elected representatives were replaced by Union government appointed officials charged with the mission of restoring the Bill of Rights and Constitutions protections to the region, as well as enforcing the newly passed 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments (abolition of slavery, equal protection, voting rights).

One hundred and thirty-eight years ago the United States government formally ended the period of occupation of former Confederate states. Military troops were withdrawn and occupation governments were pulled out. Into that vacuum rushed a power-structure that had been patiently waiting, planning, and working for just such a US Government withdrawal. Almost overnight all gains made by those of African descent were erased. The era of Jim Crow, the Ku Klux Klan, and racial segregation the likes of which had never existed prior to the Civil War, was ushered in under a black cloud of terror and threat of violence.

The culminating event of the Post-Reconstruction/Pre-Jim Crow era occurred in 1898 in the city of Wilmington, North Carolina. According to Wikipedia; “The Wilmington coup d’etat of 1898, also known as the Wilmington massacre of 1898, or the Wilmington race riot of 1898, began… on November 10, 1898 and continued for several days. It is considered a turning point in post-Reconstruction North Carolina politics. The event is credited as ushering in an era of severe racial segregation and disenfranchisement of African-Americans throughout the Southeastern United States. Laura Edwards wrote in Democracy Betrayed (2000), ‘What happened in Wilmington became an affirmation of white supremacy not just in that one city, but in the South and in the nation as a whole.’

“Originally described by European-Americans as a race riot, the events are now classified as a coup d’etat, as white Democratic Party insurgents overthrew the legitimately elected local government. A mob of nearly 2,000 men attacked the only black newspaper in the state, and persons and property in black neighborhoods, killing… 60 victims.

“Two days after the election of a Fusionist white mayor and biracial city council, two-thirds of which was white, Democratic Party white supremacists illegally seized power and overturned the elected government.” The mob who seized Wilmington by force and through murder, stayed in force. In fact they managed to motivate the rest of the state of North Carolina to elect white-Supremacist Charles B. Aycock as governor the following year.

By the turn of the 20th century, the American South and large parts of the north and Midwest, consisted of communities divided by race, enforced by threat of violence. While it was not uncommon for some whites to employ African-America female domestics inside their homes as cooks, laundresses, nannies, and maids, and to employ African-American men outside their homes as gardeners or for labor, most whites had extremely limited contact with blacks. Churches were segregated (this was not true prior to the Civil War), schools of course, were segregated, most businesses were segregated, and neighborhoods were completely segregated (this too, had not been so prior to the Civil War). Blacks, who had no power in the communities in which they lived, were forced to work for wages well-below the norm for a white person doing the same job. Economically, it was extremely difficult for blacks to buy property because banks would not make loans, and it was common (and legal) for businesses to deny blacks the opportunity to purchase property even if they had the funds.

Throughout the early 20th century, racial intimidation against blacks increased in an effort to maintain the status quo of white power in a South and in cities that were increasingly black in population. Politician’s, the press, and business owners collectively conspired to foment smoldering racism by pitting low-income white workers against black workers, keeping whites afraid of losing their jobs, and blacks afraid of losing their lives. Enforced segregation increased the gulf of understanding between the two races, keeping them apart from one another and thereby reducing the opportunity for people of different races to find common ground.

Despite all this, in the first half of the twentieth century, enforced segregation created a situation that allowed blacks to become increasingly self-reliant and self-sufficient. A vibrant black middle class emerged comprised of teachers, business owners, and eventually physicians, attorneys, and entrepreneurs. Black communities strongly emphasized education and religion, while placing a high value on a tight, nuclear family supported by extended family, and the larger community beyond. This success allowed many blacks to buy property, build wealth, and gain some political influence and autonomy. In the pre-WWII era in America, citizens of African-descent began to climb up out of the ravages of more than three hundred years of physical oppression and begin to participate economically in society that while not “equal”, was certainly far superior to anything experienced previously.

Seventy years ago, at the beginning of WWII, young black men found themselves called on by the United States government to serve their country in the War against Nazi Germany and its allies. Despite a great deal of opposition, Franklin D. Roosevelt integrated the US military, allowing men of African descent to bear arms on the battlefield for the first time since the United States Civil War. Young men fought and died in that war, defending the concepts of Liberty and Freedom on foreign shores. They performed admirably as soldiers, pilots, sailors, and marines. Their individual service records, their bravery, and their determination to prove their metal against a deeply prejudiced military population is now well-known. When the war concluded and these men returned home, they returned to communities where former POW German soldiers were served at lunch counters that they, former American soldiers, were turned away from. They, generally, were unable to reap many of the benefits of military service, as they could not be admitted to colleges that were accredited to accept VA benefits, VA home loans were closed to them, few employers would hire them, and the white communities in which they lived largely denied or ignored the fact of their service and sacrifice.

It was out of this crucible of hypocrisy and outrage that the early Civil Rights movement was born. That movement took hold through the 1950’s and into the 1960’s, culminating with Dr. Martin Luther King’s March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 27, 1963. The event made it clear to Washington, D.C., to the elected officials in Washington and throughout the nation, and to every American, that a sea-change was coming in regard to race in the country.

In the South, violence, intimidation, and white outrage was captured on television. Many American’s were horrified by what they saw. Young black and white civil rights workers were executed in Mississippi, and again, Americans were horrified. The Attorney General of the United States, Robert F. Kennedy, brought the force of the Federal Government and all-but occupied Mississippi, Alabama, Missouri, and Arkansas, and other communities during this period.

Fifty-one years ago, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed, outlawing – for the first time since Reconstruction — discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It ended unequal application of voter registration requirements and racial segregation in schools, at the workplace, and by facilities that served the general public.

Fifty years ago, Congress passed The Voting Rights Act of 1965. Per Wikipedia: “Designed to enforce the voting rights guaranteed by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, the Act resulted in the mass enfranchisement of racial minorities throughout the country, especially in the South. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, the Act is considered to be the most effective piece of civil rights legislation ever enacted in the country.”

On April 4, 1968, Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated.

With his loss, the Civil Rights movement in the United States lost its captain, its compass, its wise counsellor, and – unfortunately – its core dedication to non-violent protest. Following King’s assassination, the country erupted in a series of violent riots between African-Americans and police. The outrage felt after King’s death marked a significant turning point in the tenor of race relations in the nation. The tone quickly turned militant, frustrated, and angry. The black community divided against itself, with the older generation wanting to keep peace and pursue non-violence, while younger proponents of equal justice seeking to grasp it “by any means necessary”. The tension and the grief in black communities became palpable.

With the Passing of the Civil Rights legislation in the late 1960’s, segregation in schools, housing, and businesses, gradually became a thing of the past – for some affluent members of the African-American community. No longer forced into “Red-Lined” communities, blacks who could afford to “moved on up”, and moved out to better neighborhoods offering better school districts and greater social and economic advantages to their children. Black consumers, now free to trade with any business they chose, went out of their neighborhoods to patronize businesses with better selections, perhaps lower prices, and all certainly offering a novel experience as compared to their well-known, local black merchants. White consumers, by contrast, did not flock into black neighborhoods to seek out the novelty of segregation.

Rather, middle class whites who found their neighborhoods and schools gradually including blacks, fled to the suburbs and opened private “parochial” schools that could, legally (and more important to the individuals of that era and our own, use religious “morality” to) discriminate on racial grounds.

Between the passing of Civil Rights legislation in the late 1960’s and the beginning of the Reagan administration in 1980, the once-vibrant black middle class which had steadfastly taken care of its own, all but vanished in what remained of the still segregated nation. Black businesses failed due to lack of customers, and so black employment in the community ceased. Black schools were absorbed into white school systems which were abandoned by the tax base and left to ruin. Historically black colleges saw enrollment gradually decline, and then precipitously fall into oblivion as the few black students who could go to college, chose to go to integrated colleges and universities offering a wider range of scholarly options. Middle-class blacks mainstreamed into the larger society. They represented a small percentage of the African descent population in the United States, but their absence in still-segregated communities was felt all-too-keenly. This group included teachers, professionals, doctors, and attorneys – the leaders of what had once been a wholly segregated community. When they left they took their values of education, hard work, self-respect, wisdom, and self-discipline with them. What remained in those neighborhoods, towns, and cities was an impoverished class of poorly educated residents with few economic options, little education, and no one remaining to look to for guidance or for employment.

After the Vietnam War concluded in 1975, another generation of African-American veterans returned home to conditions even worse than those experienced by their fathers a generation before. They came home to broken communities that offered no jobs and no recognition of the sacrifice they made. Many vets, black and white, returned from Southeast Asia with drug addictions (courtesy of the CIA). And black vets were returned to neighborhoods already saturated with the first wave of Cartel-scale drug dealing.

Thirty-five years ago, under the administration of President Ronald Reagan, the “War on Drugs” was commenced in response to the increasing crime rate and lawlessness experienced in the country, which the President blamed on drug users, dealers, and neighborhood gangs. During this period the “3 Strikes” mandatory sentencing was imposed in many of those states with the largest percentage population of African-Americans. Interestingly, the myriad of legislations written and adopted by states targeted crack cocaine (predominately used by African-Americans) for much harsher, longer sentences, while leaving rock or powdered cocaine (primarily used by whites) as lesser offences. At the same time that the President lectured the American people on the evils of marijuana and crack, members of his administration were participating in “guns for drugs” exchanges with Central American dictators (the “Iran-Contra affair”), bringing marijuana and cocaine into this country, then dumping it into African-American communities on the wholesale.

Twenty-years ago, both federal and state governments began to investigate the concept of mass-privatization of prison systems. The early experiments generated a windfall of profits to both the states and the companies hired to run private, for-profit prisons. Private companies were contracted to run large, industrial scale prison systems nationwide. They worked in partnership with law enforcement and the judiciary to ensure a constant high population count in these facilities. With the assistance of drug laws passed a decade earlier (almost in pre-cognition of the Private Prison concept), a new, multi-billion dollar industry cropped up without anyone really noticing – except young black men and their families.

For the whole of the United States population, the prison statistics are sobering. From 1980 to 2008, the number of people incarcerated in America quadrupled-from roughly 500,000 to 2.3 million people. Today, the US is 5% of the World population and has 25% of world prisoners. Combining the number of people in prison and jail with those under parole or probation supervision, 1 in every 31 adults, or 3.2 percent of the population is under some form of correctional control.

— African Americans now constitute nearly 1 million of the total 2.3 million incarcerated population, with an incarceration rate at nearly six times the rate of whites.

— Together, African American and Hispanics comprised 58% of all prisoners in 2008, even though African Americans and Hispanics make up approximately one quarter of the US population

— One in six black men had been incarcerated as of 2001. If current trends continue, one in three black males born today can expect to spend time in prison during his lifetime

— Nationwide, African-Americans represent 26% of juvenile arrests, 44% of youth who are detained, 46% of the youth who are judicially waived to criminal court, and 58% of the youth admitted to state prisons (Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice).

— African Americans are sent to prison for drug offenses at 10 times the rate of Whites.

— African Americans represent 12% of the total population of drug users, but 38% of those arrested for drug offenses, and 59% of those in state prison for a drug offense.

— African Americans serve virtually as much time in prison for a drug offense (58.7 months) as whites do for a violent offense (61.7 months). (Sentencing Project)

Three years ago, an un-armed, black teenager was walking through his home neighborhood with a soft drink and a snack. He was followed, assaulted, and shot to death by an armed private citizen who claimed the young man looked suspicious. The armed man was not charged in the murder of Trayvon Martin. He went on to commit numerous other assaults and violations of the law, yet he has yet to serve any time in prison for his offenses.

Since Trayvon Martin’s death, countless private citizens armed only with cell-phone video cameras have captured live-action incidences of abuse, assault, and even murder, committed by police against un-armed African-American men and boys, as well as against “petty criminals” who posed little if any genuine threat to society. And yet, few, if any officers have been prosecuted.

Not quite two weeks ago an unarmed, twenty-five year old African-American man who was guilty of simply running through a neighborhood parking lot, was accosted by the Baltimore Police, detained, arrested, and – somewhere between his run and winding up in zip ties, face down on the pavement, had his spine severed, leading to the loss of his life. Much of the incident was caught on cell-phone video, and it’s fairly clear to any rational person that Freddie Gray, the victim in this instance, was already severely injured when the police hauled him, legs dragging behind him, into the police van.

Another young man headed to prison or to the grave? Another son, father, brother, stolen from his family.

Four hundred years ago, our ancestors began importing native black Africans from their home continent to the North American continent, in chains, shoved below the decks of ships built especially for the purpose of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Today we – our current generation – import African-Americans into the for-profit prison system, using a hyper-militarized police force trained for this express purpose, and a judicial system built to ensure the success of the current system – a system which seeks to enforce the status quo – where black families are broken and kept weak and leaderless, where black bodies are used for profit, and in which Black Lives Don’t Matter, except for what we can get out of them.

With a history such as this one, a few riots every few years are to be expected. It’s nothing new. It’s been going on for 400 years and until we (the white people in power) recognize that the system in place is not broken, that in fact it is doing exactly as it was designed to do, nothing is going to change. Except we should keep in mind, every 200 years or so, the slave rebellions actually succeed. It’s something to think about as we contemplate this highly successful system we’ve all become so accustomed to that we can no longer even see it clearly for what it is – a criminal enterprise.

One day while strolling leisurely along the dockside of Liverpool, I heard two boys converse together, which attracted my attention. One said to his companion that the American ship St. Lawrence, of New York, lying in the Princess Dock, wanted a boy; that he was going to see if he could secure the place. This was near dinner time. After dinner I went down to that ship, and saw the mizzen royal flopping in the wind. This is the loftiest of the fourth sail on the third mast. One of the big boys spoken of was on his way up the rigging to furl this sail. He seemed very clumsy and slow getting up the rigging, and when he got up did not know how to gather the sail together so as to make a neat job of it. I noticed a man whom I learned was the chief mate, watching him from the dock. After he had made several attempts, the mate called him down. The boy walked off crest-fallen. After he had disappeared, I walked up to the mate, thinking that this was his way of finding out what a boy could do, I asked him if I could go up and furl that sail. He asked where I had learned to furl such sails. Answering him that many times a day in the Mediterranean it was my business to furl the royals, while the men were at the heavier sails. He doubted that such a small boy as I was could furl such sails in heavy winds. It was blowing quite stiff at this time. Finally he said I could try. I went aboard, doffed my jacket, and went up the rigging one a trot, getting out on the royal yard, gathering the sail on one side and then the other, passing the gaskets around, gathering the slack of the sail in the center, passing around a netting made for that purpose, I had the bunt in the center like a drum, all in ship shape. I descended the rigging as lively as I went up, picking up my jacket and walked where the mate stood, watching my every movement. He also walked towards me without saying a word, handing me a card which instructed the shipping master who was shipping a crew for this ship, to place me on the list. There were many of these shipping masters in Liverpool, as well as every large seaport. When a ship has taken in all her cargo, the captain a few days previous instructs one of these shipping masters to ship so many men for his ship, to sail on such a day for such a place. Master-riggers with a gang of men having bent all the sails, examined all the rigging, replacing all the defective, you will understand this was an American ship, all hands had abandoned her, when in fact they had no right to leave until she arrived at some designated port in the United States. When men are not properly treated, they abandon their ships at the first opportunity. This was the case with the St. Lawrence. Not one left but the captain, first and second mates.

One day while strolling leisurely along the dockside of Liverpool, I heard two boys converse together, which attracted my attention. One said to his companion that the American ship St. Lawrence, of New York, lying in the Princess Dock, wanted a boy; that he was going to see if he could secure the place. This was near dinner time. After dinner I went down to that ship, and saw the mizzen royal flopping in the wind. This is the loftiest of the fourth sail on the third mast. One of the big boys spoken of was on his way up the rigging to furl this sail. He seemed very clumsy and slow getting up the rigging, and when he got up did not know how to gather the sail together so as to make a neat job of it. I noticed a man whom I learned was the chief mate, watching him from the dock. After he had made several attempts, the mate called him down. The boy walked off crest-fallen. After he had disappeared, I walked up to the mate, thinking that this was his way of finding out what a boy could do, I asked him if I could go up and furl that sail. He asked where I had learned to furl such sails. Answering him that many times a day in the Mediterranean it was my business to furl the royals, while the men were at the heavier sails. He doubted that such a small boy as I was could furl such sails in heavy winds. It was blowing quite stiff at this time. Finally he said I could try. I went aboard, doffed my jacket, and went up the rigging one a trot, getting out on the royal yard, gathering the sail on one side and then the other, passing the gaskets around, gathering the slack of the sail in the center, passing around a netting made for that purpose, I had the bunt in the center like a drum, all in ship shape. I descended the rigging as lively as I went up, picking up my jacket and walked where the mate stood, watching my every movement. He also walked towards me without saying a word, handing me a card which instructed the shipping master who was shipping a crew for this ship, to place me on the list. There were many of these shipping masters in Liverpool, as well as every large seaport. When a ship has taken in all her cargo, the captain a few days previous instructs one of these shipping masters to ship so many men for his ship, to sail on such a day for such a place. Master-riggers with a gang of men having bent all the sails, examined all the rigging, replacing all the defective, you will understand this was an American ship, all hands had abandoned her, when in fact they had no right to leave until she arrived at some designated port in the United States. When men are not properly treated, they abandon their ships at the first opportunity. This was the case with the St. Lawrence. Not one left but the captain, first and second mates.

You must be logged in to post a comment.