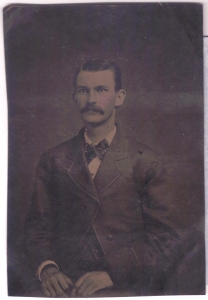

William Ellis Jones and his young son Thomas Ellis Jones

William Ellis Jones (1899 – 1951)

William was born at “Summerfield” on August 7, 1899. We’ve already learned a great deal about his parents (F. Ellis Jones and Addie Gray Bowles) and his grandparents’, their lives and their deaths; therefore I’ll begin his story as best I can, opening with the few details of his life that I know of as fact.

William enlisted in the US Army on October 3, 1918 – precisely eleven days before his mother died from the Spanish flu. He was just nineteen years old. The Army records indicate that he was in good health, of fair complexion with blue eyes and light colored hair, and that he was five feet, five inches tall. He was honorably discharged from the Army on December 9, 1918, having served just two months. (World War I was just concluded and the Army didn’t require his services any longer.)

We know that his occupation was listed as a “student” on his enlistment record, but neither he or my father left a record that indicates where or when he attended college. That he did attend and graduate college is relative certainty, as he was earning his living as a school teacher by 1923. Though it’s not recorded by anyone as far as I can determine, my father told me that his father taught high school English, which makes sense.

I know that his grandfather’s business, William Ellis Jones & Sons, ceased to exist under that imprint in 1919, after almost fifty continuous years of publishing under “Jones” in one form or another.

On October 20, 1923, he married Dora Georgia Thomas of Chesterfield County, Virginia. She was just fifteen years old, and she was one of his high school students. The specific school she attended and where William taught her are not recorded, although family lore indicates that she attended, and he was teaching at one of the Chesterfield County schools when they met.

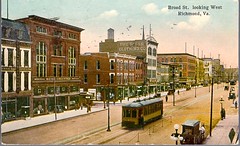

Their first child, Dora Ellis Jones, was born January 11, 1925 in Pulaski, Virginia. William was teaching in Pulaski at the time. Their second child, Thomas Ellis Jones, was born May 1, 1930 in Richmond, Virginia. Their third child, Georgia Ellis Jones, was born April 7, 1933 in Richmond, Virginia. At the time of the births of his last two children, it appears that William was trying his hand at making a living as a writer, but he may also have been teaching in Richmond to supplement his income.

William apparently began his first draft of the family history that eventually became The Baby Book in 1930, if not before. He did not conclude it until 1936 or possibly later. He wrote a good portion of the document from New York City, where he was working as a stockbroker up until late 1935 or 1936. In addition to his “day job”, William also worked consistently on writing plays; usually one or three act comedies that he had some success in getting published. From 1932 to 1948, he had at least twenty-eight plays published by at least ten different publishers.

At some point prior to 1935, William and Dora’s oldest child, Dora Ellis, became gravely ill. It’s not recorded exactly what her ailment was, but it was debilitating. The physicians who attended her advised her parents to remove her from the northern climate and pollution of New York City in order to improve her condition. William tried to organize his small family and his smaller finances in order to make a move to Florida, but for unknown reasons their plans to relocate south were delayed. Dora’s condition worsened as the weeks passed, and before William could get the family moved out of New York, his daughter died on June 3, 1935. She was just ten years old.

The death of his little daughter Dora Ellis was absolutely crushing.

It’s at this crucial moment in this little family’s history where facts, family lore, and supposition conflate into a sad and very confusing story.

Before we go forward, however, we need to go back.

——-

William’s Grandfather was a successful man of excellent reputation who owned two very nice homes and a thriving business. The printing business continued to function – under his imprint – for eight years after his death. We know that F. Ellis involvement in the business ceased after his death in 1910, but his 1/3 interest in the business would have passed to his wife, Addie Gray, and then after her death, to her only son William. Addie Gray died in 1918 – precisely when we see “William Ellis Jones & Sons” cease to exist.

The way I see this scenario played out is that William Ellis Jones (1838 – 1910) left his printing business in shared partnership to all three of his sons. No one of them could force a buyout of the other unless all three “partners” agreed. When F. Ellis Jones died in 1910, his share passed to Addie Gray, and she – needing an income to support herself and her son – refused to be bought out. The properties in Richmond and at Dumbarton were probably willed in the same fashion; giving life rights of occupancy to any one heir or all three, but preventing the disposal of the property without the agreement of all three in unison.

The other two Jones brothers, Fairfax and Thomas, probably wanted to buy out their deceased brother’s portion, but they could not coerce his wife Addie Gray to move. She would have continued to draw an income from the business for eight years after her husband’s passing, and continued to have a life right to the house(s) as long as she lived. Upon her death this same right would have passed to young William.

When Addie Gray died, Fairfax Courtney Jones and Thomas Grayson Jones made their move. William, their nephew, was just nineteen years old and had just enlisted in the Army – fearing he would be sent to Europe – and still reeling from the death of his mother, his grandmother, and Aunt “Deitz”. He had never worked in the printing company and had no sense of its value. Nor did he probably even understand the papers that were put in front of him by his uncles, or just how small the check they gave him was.

William goes from being a fairly well-to-do teenager who floats between two homes and has access to everything he needs – to a young man who is scraping by from job to job, borrowing money from his grandfather’s old friends (this he admitted in The Baby Book!) and within fifteen years of his Mother’s death is so destitute that he cannot pull together enough cash to save his daughter’s life.

I propose that William was swindled out of a substantial portion of his inheritance by his uncles (who, interestingly, he barely mentions in The Baby Book.) I further propose that any money or investments he still had remaining by 1929 were completely wiped out in the Stock Market Crash. I believe that’s why he was in New York in 1935 – trying desperately to win back his lost money. If this is the case it was a desperate maneuver, as he had no natural talent or training in that arena. If that is what he was attempting – he failed miserably – in truly tragic ways.

William probably blamed himself for taking the family to New York where Dora contracted her illness, and for getting them into such financial straits that they could not leave when they needed to.

Mr. Hyde – or Dr. Jekyll?

This is where the story gets really confusing, and why police officers seldom believe eye-witness accounts of accidents and crimes. Two people standing side by side on the same street corner will recall the same event with vastly diverging details – and they both claim that their story is the absolute fact of what happened.

After Dora’s death, William had two living children remaining. The oldest, Thomas Ellis, was five years old when his sister died. His younger sister Georgia was barely two. Neither of them would have retained enough memories of the actual events surrounding her death to be able to offer any precise information on the matter, or to say with certainty what either of their parents’ emotional state was in the aftermath.

What’s more interesting though, is that Thomas Ellis Jones, his son and the older of the two, recalled almost nothing of the event – and was reluctant to even discuss the subject – only saying that it was something his father “never got over.” Georgia, on the other hand, did discuss the loss of her sister (a sister she never knew) with her children and grandchildren. And she went even further and explained the death of this girl as the reason that her own childhood was miserable.

Thomas, when asked about his father, would light up like a Christmas tree and start recounting vivid, happy memories. He had so many stories – each one more grandiose than the next – that I truly suspect the voracity of any of them. I do know that he worshipped his father and believed him to be a nearly genius writer. (Except for the single poem that is quoted in Chapter I of the book, Stumbling in the Shadow of Giants, I have seen little of his work that would qualify as genius, but I am a hard critic, and I have not seen much of his work beyond his plays.) Thomas spoke glowingly of William Ellis Jones. I think he truly believed his childhood was happy, and that he was adored by his father.

His one negative word in regard to his father had to do with alcohol. He said that his father drank too much, and that the disease ran in the family. This was given to me with gravity when I was well past thirty years old, when I offhandedly mentioned on a call that I was going “out to the bar” with friends later that evening. It was a figure of speech in the company I kept at the time, and probably did not mean the same thing to me as it implied to him. I heard the concern in his voice and I filed the information away for future reference.

Twenty-years later I tracked down the children of Georgia Ellis Jones. Georgia passed away in 2007, and so she could not be interviewed, but Georgia’s daughter, who had nursed both her mother and her grandmother (William Ellis Jones wife, Dora Thomas) through their last days, was more than willing to share. She did not know William Ellis Jones either. She heard of him only through the recounting of her mother and her grandmother. The picture she painted for me was one I had not been prepared for, given the glowing words Thomas always laid down when he talked about the man.

I will not go into absolute specifics, but in essentials the story is as counter to what Thomas reported as any could be. The only points the two positions agree on is that William Ellis Jones did drink too much. From Georgia’s perspective this over-indulgence manifested itself in blind drunken rages in which he beat his wife and his daughter within an inch of their lives. I was told that when these fights occurred, Thomas (her brother) would lock himself in the bathroom or in his bedroom – with a book. Or he’d simply leave the house if he could get away without getting involved. She said that afterward both he and his father acted as if nothing had ever happened, and it was never talked about.

One specific that I do think is worth mentioning; Georgia told her daughters that William blamed Georgia for Dora Ellis’s death, and when he would get depressed and drunk, he’d tell her that it was her fault and he wished that she had died and not Dora…

…All this begs the question – how much pain and loss can one person endure before he breaks?

William knew profound loss; the loss of every blood relation he had in a very short span of time, at a very formative period in his life. He lost both his father and his much beloved grandfather at ten years old, his adored Aunt “Deitz” at sixteen, his mother at seventeen, and finally his grandmother at nineteen. That is too much for one young person to endure. But then he lost his place in society, his financial security, and finally his little daughter. It was just too much.

He was a shattered man. He had no tether to anything substantial whatsoever. He was just running.

From the point of Dora’s death onward, the family story is one of constant movement. First, they relocate to Miami Florida; the plan to get to a warmer climate finally coming together some months after Dora had already passed. They stay in Florida until about 1939, then they return to Virginia. William taught school in Clarksville, Virginia; then back to Pulaski; then in Richmond; then in Wytheville. By 1951 the family was in Bristol, Virginia, and Thomas Ellis, his son, was in the Air Force hoping not to get sent overseas to Korea.

On July 29, 1951, William sat down in his favorite easy chair with a glass of Kentucky Bourbon, a book, and a piece of dark chocolate. He died with the drink in one hand, the book in the other, and the chocolate still melting on his tongue.

Or so my father said.

Whatever the case, I like this version of his passing. It seems as good a way to slip over to the other side as any way I can think of. William’s pain finally saw an end; and a peaceful end at that.

Unfortunately he still had two living children who carried the seeds of his pain with them….

———————————–

To learn more about William Ellis Jones, his life and his descendants, see the forthcoming book Stumbling in the Shadow of Giants, by C.H. Jones.

———————————–

You must be logged in to post a comment.