The following article appeared about 1935 in the short-lived, progressive newspaper “State’s Progress”, which was published in Durham, North Carolina in the 1930’s. The subject of the interview was Sally Parham, who was born before the Civil War on Asa Parham’s plantation , near Tabbs Creek, just east of Oxford, North Carolina. Asa Parham was my cousin, the relation coming through the Crews line down to my own. The existence of this slave narrative first came to my attention through “North Carolina: The Subtle Politics of Slavery Before and After the Civil War” at BC Brooks: A Writer’s Hiding Place.

‘Black Mammy’ Tells Graphic Story of Slavery

By Charlotte Story Perkinson

Article that appeared in “State’s Progress” newspaper about 1933 – Image courtesy of bcbrooks.blogspot.com

Dr. John Spencer Bassett has said; “The lives of the American slaves were without annals, and to a large extent without conscious purpose. To get the story of their existence there is no other way than to follow the tracks they have made in history of another people.”

But an effort to obtain a true picture of the period by talking directly to the actors in the drama themselves, as I have done at every opportunity, is fraught with difficulties, one of which is that the memory at 90 and over is apt to be much impaired, and another that even 75 years after the Emancipation Proclamation, there is still a great tendency among these old darkies to say only those things pleasant to the ear of the descendants of former slave owners. This hesitancy in revealing the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, probably comes from incentives of fear of fear and loyalty combined. Usually these old slave brag about the wealth and social prestige of their masters, and try to keep alive something of the glamorous, but not altogether true picture of old plantation life. Only two out of many I have interviewed have revealed anything of the ugly or the evil in the setting.

Even so, it was not without advantage to the negro to have come to America as a slave, according to Booker T. Washington, who says; “It was the negro’s task to learn from experience by his contact with most advanced types of experience in the history of man.” That he has performed and is still performing that task well cannot be denied.

Is 102 Years Old

“Black Mammy”, so called for generations by all who know her, is by far the most interesting survivor of the old order I have yet talked with.

She is 102 years old, and says that she knows this to be her age, because she was born the same year as so and so of her master’s children, whose births are recorded in the family Bible. All of the children referred to are dead years ago.

Her name is Sally Parham, and she belonged to Asa Parham, who owned a large plantation five miles from Oxford on the Oxford-Henderson road in Granville county. She has served five generations of the family, and now, totally blind, is being cared for by a great grand-daughter of her master, Mrs. Elizabeth Dorsey Walters, whose mother was Cynthia Parham, daughter of Gaston and granddaughter of Asa Parham.

Aunt Sally not only related not only the more or less familiar story of having a good master, how and when she got religion, her memories of the Civil War and the part she played during that period, but she gave a most revealing description of the slave speculator, of how crime was punished, of the “pattyrollers”, and of many other subjects not often touched upon. Truly she seems like a character taken from the pages of history unwritten, because almost everybody she knew and who form a part of her story are long since dead, she would often rather pathetically exclaim, “O Lord, I live in de grave yard now.”

Always Same Plantation

This old woman lived her entire life on the same plantation until 1928, when the land was again divided, with the exception of a short time following her master’s death.

Then she became the property of Nan Parham, who married a Bobbitt, and went to the Bobbitt home to live. Here, she says, she was so homesick that she ran back home, and to satisfy her, it was finally agreed among the heirs to let her remain at the old place and cook for the five bachelor sons, they agreeing to pay her wages to the “Legatees” as she expressed it.

“Black Mammy’s” earliest memories take her back to the time when she first went to the big house to be trained as a house servant. When her mother came after her, she says she refused to return to the slave quarters, and was dragged down the front steps, “My head counted those steps, and I’ll never forget them,” she said.

Sometimes, when she was still a child, she told me, her white mistress sent her to school with the white children. She was given a note to the teacher with instructions to let her have some books. One was a “Blue Back Speller” from the pages of which she spelled several words for me from memory, syllable by syllable. She also repeated the alphabet and said she was proud of her education and wished she had not dropped it so soon.

“Black Mammy” was only married once. But of course marriage in slavery days was hardly more than an agreement to live together, and the institution of slavery was conducive to polygamy, inasmuch as the more children a slave woman had the more value she was to her master. Aunt Sally’s ideals in this regard were quite high, however, and patterned after those of the white folks. Her husband was Harry, a slave belonging to Albert Parham, and living on the adjoining plantation. If she had any children, they as well as her husband are all gone, while she lives on way past her age and generation, reenacting in her imagination the scenes of a by-gone day.

Meeting Houses For Slaves

Aunt Sally says that while the assembling together of the slaves was carefully guarded against, fearing an uprising, the Parham brothers, whose plantations joined and who owned a large number of negroes, built a meeting house where their slaves could hold prayer meetings and other religious services. This house was across the creek from her master’s place, and when slaves went to it, a colored overseer was usually sent along with them.

One night Black Mammy wanted to go to a prayer meeting and her father raised objections. There was a scene and chastisement. It was then and there she says she got religion, right at the foot of a walnut tree in her Mammy’s back yard. “No one dar’ but me and Gawd!” She joined the white folks church, called “Tab’s Creek” and was baptized in Cheatham’s Pond, along with about 20 others, which included members of both races, she told me.

One means employed for keeping the slaves from congregating together and possibly plotting mischief was the institution of the patrol, the “pattyrollers”, the slaves called them. The patrol consisted of five white men or thereabouts, appointed by the local unit of government, whose business it was to see that slaves were on their own mater’s plantations after sun-down.

Had To Have Pass

If a slave went courting or to a candy stew or to a prayer meeting or on an errand for his master or mistress, it was necessary for him to have with him a note or pass saying who he was and where he was going. Slaves caught away from home without permission were given a whipping and sent home. They feared and hated the “pattyrollers” intensely and they used to sing a song about them which went like this;

“Run, nigger, run de pattyroll catch you,

Run, nigger, run fo, it’s almost day!

Massa was kind an’ Missus was true,

But if you don’t min’ de pattyroll catch you!”

It appears that the patrol was not much respected by the slave owners either.

The old slave laughed as she related how some slave and white boys used to play pranks on the “pattyrollers”. She said one night they stretched ropes across the lane leading to the negro quarters and then hid and waited for the gallop of the night patrol. Soon they heard each horse fall with a heavy thud, one after another as the rope tripped them. Needless to add there were no boys of either color visible when once the riders and horses set out again upon their spying errand.

Without doubt the most despicable feature of the institution of slavery, and the thing which aroused the abolitionist the most, was the slave trader, or slave driver, or “speculator”, an abominable species of humanity who trafficked in black flesh, who sold and bought men, and women and children for profit.

The slaves hated to see the speculator wagon drive up. The wagon was covered with canvas and drawn by several mules. Into it were herded much as sheep or dogs might be, often as many as 17 unwashed and half-clad negroes.

One particularly pathetic scene has fixed itself upon the memory of “Black Mammy’s” memory. It was of seeing her husband’s brother standing by a tree and begging his master to sell him. His wife and children had already been loaded into the trader’s wagon.

“Massa, please sell me too. I’ll never do you no mo’ good, please sell me,” the miserable darky begged.

“I don’t want to sell you, Tom.” The master replied, kindly. “I like you. You’re a good servant.”

But the speculator kept offering more and more money for him, until finally the master relented and let the poor wretch join his wife and children in the slave wagon, only to be separated again, no doubt, perhaps at the next plantation.

“Why was the wife sold?” I wanted to know.

“Cause she had Injun blood in her,” was the reply. One can imagine that genuine negro blood would better serve the purposes of slavery than mixed blood, negroes being more docile and more trustworthy than Indians. The blackest skin brought the highest price, “Black Mammy” said. Negroes and Indians did not get along well together.

The old slave women related two extremely interesting and dramatic incidents illustrating how crime was punished when she was young.

One was the story of Martha and Joe, two slaves who murdered their master by scalding him with boiling coffee, and who were made examples of by hanging in the courthouse square. All the negroes from far and near were forced to witness the scene.

To See Hanging

“I was piled into a wagon with many other black folks,” said “Black Mammy”. “I was scared almost to death and kept up such a yelling and screaming that my master finally said, ‘Put the little fool out.’”

“My mother went on just the same,” she continued, “and said she couldn’t sleep any more afterwards until she got religion.” Times without number she heard her mother, and others, describe the pathetic scene.

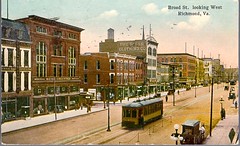

The hanging took place at Harrisburg Creek, where the courthouse used to be located.

Martha, a young black woman, sat upon her coffin with a rope around her neck. At her breast, being fed, was a little black baby, born while she was in jail awaiting execution. A few minutes before the time set for her death, as is almost invariably the case with negroes under great emotional stress, she broke into song;

“I’s travellin’ to de grave my Lawd,

To lay dis body down.

Sister, you’d better watch and pray,

I’m huntin’ for Jesus night and day.”

As she finished the verse, someone in the crowd hollered out, “You ought to athought a that ‘fore you scalded your moster.”

The poor creature begged for time to sing one more verse, and continued her song. Then hurriedly handing her baby over to a black woman standing by, she sang on until the suddenly taughtened rope choked out the sound.

Martha and Joe were kitchen servants. They felt that their master was cruel to them, which of course in no way justified their act. Their mistress was dead. One day while they were busy in the kitchen preparing a meal and their master lay asleep in an adjoining room, snoring loudly with his mouth wide open, they conceived the idea of scalding him by pouring boiling coffee down his throat. This they did, and he was so badly burned that he soon died.

It seems that when a slave killed a white man he was dealt with in short order, and made an example of. But when the state took the life of a slave, it had to make restitution to his owner, in the same way that a corporation nowadays has to pay damages for injury to property, perhaps for running over a horse or a cow. Slaves were property then, in exactly the same way that a horse was.

On account of having to pay the master for his value in dollars, a slave who committed a crime against another negro was not often punished by death. Neither was he always cast into prison, for by so doing, the master would still be damaged in that he would be deprived of his labor. Consequently many and devious ways were prescribed for punishment, some very cruel. The law often set so many lashes for this and that crime. But there were punishments far more devilish and barbarous than whipping. Take, for instance, the story “Black Mammy” related for how a black youth was punished for killing his father.

There was a party in progress on a certain plantation. Fat lightwood knots and handmade candles augmented the light from open fires. Considerable drinking was going on, and a negro named Jack went to get another piece of lightwood from his father’s supply. The old man evidently thought it was time for the party to break up, so told his son not to get any more, and stood in his path in an attempt to keep the young man from doing so. In a fit of drunken fury, the son kicked his father in the stomach and killed him instantly.

Branded in Palms

The young negro was punished by being taken to a nearby blacksmith shop and tied to a stake. Then he was forced to hold out one hand while a red hot iron was applied to his palm long enough for him to repeat three times slowly and distinctly – “The Lord save the state – The Lord save the state – The Lord save the state.” Then he had to hold out the other palm and again repeat the words as before three more times. Of course he tried at first to say the words as fast as he could, but for so doing he was stopped and made to begin over and repeat them slowly after his tormentor, who applied the branding iron. This man could not use his hands for a year, “Black Mammy” said. And in order to prevent his own brothers from killing him, his owner sold him to get him out of the way.

Aunt Sally told me about the first train which came through the section, and described the first cook stove she ever saw. She said this stove was used in Oxford’s first hotel and was so big it looked to her like a wagon. The old negro attributes her blindness to weakening her eyes by cooking in the smoke over a fireplace for so long. She did not become totally blind, however, until two years ago following an attack of influenza.

Of her experiences during the War Between the States, she says that she and her husband took care of the place while her young masters went to war, that she carried their money on her person, and hid it about at different places at different times. She said they buried the meat and valuable in ditches, and laughs at how many times she fooled the Yankees. One time she said she put the molasses in front of the liquor jugs. She says she outwitted them many times and managed to keep her master’s money and guns and other valuable away from the invaders until their return from the conflict. For her loyalty during those trying times and always she has been rewarded by being cared for by her white folks ever since.

Never Forgets Manners

This quaint old figure in her white cap and black and white dress, even though living in the same house with her mistress, is in no way presumptuous and never forgets her manners. They are those of old slavery time, when the finest points of etiquette were observed by the white people, and whose manners were imitated by the house servants generally. Even in her blindness, “Black Mammy” is able to do many things for herself. Her mistress has to lead her from one room to another and give her medicine, in the nature of a heart stimulant.

Even now the old woman feels it within her province and a part of her duty to the old family, to admonish and advise her young mistress, when occasion demands, and most of all to tell her “‘bout the way her family did and lived befor’ de war.”

She referred to the intermixture of the races as the greatest curse of slavery. While she said the practice of a slave owner keeping a negro mistress, who bore him mulatto children, was not universal, it was not unusual, and was the cause of a great deal of misery and unhappiness for both races concerned.

“Black Mammy” ended her talk by saying; “It’s de truth, de Gawd’s truth. I’d be afraid to tell lies ‘cause I spec to go up yonder ‘fore long now.”

END

—

[Eds Notes: A search for records on Sally Parham of Granville County, North Carolina tuned up a death certificate dated February 18, 1937. She died at the County Home in Granville County, of Pneumonia complicated by cardio arrhythmia. On the form, in the box labeled “age” is handwritten 105. In the box with the cause of death notes, the number 107 is written large and encircled. In the box for birthdate, there is only a handwritten X. In the box requesting her husband’s name, on the word “widowed” is written. Her race is listed as “colored”. The burial place is difficult to decipher, but upon careful study and comparing the letter forms with other known words written on this document, I have determined that it reads “Antioch Church”. This would be Antioch Baptist Church in Granville County, NC. Her grave is apparently unmarked. Her father is listed as “Andrew Parham”. Her mother is listed as “Nancy Revis”, both of Granville County. Note that the “Reavis” (note spelling variation) family of Granville was intermarried with many of the prominent Granville families, including the Parham’s, the Hunt’s, the Kittrell’s, and the Cheatham’s. This person declared in this death certificate is undoubtedly the “Aunt Sally” or “Black Mammy” described in the article above. See a scan of this document immediately below.]

Death certificate of Sallie Parham, who was born a slave on Asa Parham’s plantation in Granville County, North Carolina, and died at the age of about 106 in the County Home in nearby Oxford.

You must be logged in to post a comment.