AUTHORS NOTE: Since drafting the entry below, new facts have come to light which COMPLETELY DEBUNK several ideas put forth here in. Rather than “erase” or delete my mistakes, as if they never happened (which occurs all too frequently on the net), I have chosen to “redact” them by crossing through the patently false, or overly speculative portions of the text. For more information, please refer to my post “Epic FAIL | Confessions of a highly speculative genealogist“.

An Apology

It’s not my habit to begin any endeavor with an apology; however this effort demands it.

First; I never intended to delve too deeply into the life of Goronwy Owen, as I contemplated what should be included in this book. His life and work was to me, too complicated, too important, and too well-documented for a novice like me to even attempt it. But try as I might to leave Goronwy in the mists of epic Welsh myth, Goronwy would not leave me alone. He and his kept coming back to haunt just about every era and every other personality I touched upon as I researched and put together the drafts of my project.

Right from the beginning of my little biography of Goronwy Owen, I start with my right hand tied behind my back. Owen’s history is a complicated one, and an important one to those who care deeply about the Welsh language and its literature. He, along with his patrons and closest friends; Lewis Morris, Richard Morris, and William Morris, are largely responsible for the Renaissance in Welsh letters that began in the 18th century. That said, almost all of their correspondences, as well as the vast majority of the poetry they created, remains un-translated from the Welsh into English – and I remain wholly ignorant of Welsh.

As I contemplated this project, I struggled within myself as to whether it was even appropriate to conceive it, given my ignorance of the language this man loved, lived for, and eventually died with as his sole companion. I considered it an arrogant and conceited thing to do, to try to write anything about him when I can not read a word of anything by him. Yet as I write about my ancestors and I piece their stories together, I keep coming back to Goronwy Owen and he keeps coming back to me.

He’s a seminal figure in my own family’s drama from Merioneth, Wales to Virginia. As I turned to my resources on Owen, I found they were often contradictory, piecemeal, disorganized, and basically just difficult to get through. I had to take the story apart and put it back together in order to understand it completely. The result is what you see – as imperfect as it is – I hope it will provide a side of the story that the man himself never had an opportunity to tell.

I beg your pardon for the incompleteness of this effort.

—————-

Goronwy Owen is considered by a great majority of Welsh scholars to be the most gifted poet and linguist of the 18th century; perhaps of all time. He, along with his patron and friend Lewis Morris, almost single-handedly rescued the Welsh language and the Welsh bardic tradition from extermination. The then-fragile language faced determined and well-armed enemies charging from every direction, including; the Church, which enforced English in its services, records, and schools, and thwarted all opportunities for Welshmen to excel in its ranks; the Government, which conducted all official business in the country in the English language exclusively; from a struggling population who too easily dismissed their own heritage for the expediency of progress, adopting English or ugly “Wenglish” hybrids which were no real language at all; and finally (perhaps worst of all), from forgers and inventors, who lacking any genuine knowledge of the antiquity or etymology of the tongue, invented a false one along with fake literature to support their fiction.

Goronwy Owen; an impoverished ne’r-do-well from remote Anglesey in the far north of Wales, thwarted the English and Welsh Church, thwarted the English Government, thwarted those without a vision for Wales, and thwarted the forgers. Unfortunately he never knew of his success. He never knew that he became a hero and a legend among Welsh patriots and literatures. Since his death in the 18th century, his story has devolved into something almost mythic.

It’s the purpose of my small biography to leave the mythic behind; let the flowery prose of admirers of his poetry have that part of his story to themselves. I simply want to lay out a coherent account of what the man did with his life, how he did it, and what became of him and his descendants. That’s the best I can do.

—–

Goronwy Owen’s Youth

Wales is a remote country. Anglesey is more so. It’s an island on the far northwest coast of the country, separated from the main by the Manai Strait in the south, and by the Irish Sea on the west, north, and east. In the east central part of the island there is a small village known as Llanfair Mathafarn Eithaf. It sits just inland from the coast, and very near a great tidal sand flat that is among the most beautiful and unique spots on the planet. Behind the village the coast rises quickly skyward and Anglesey’s many mountains and forests create a scenery that has inspired poets for centuries. It’s a truly magical place near where, according to myth is one of the places where King Authors Round Table met.

Goronwy Owen was born in this magical place on New Year’s Day, 1722. [1]

His mother was named Sain Parri, and according to the old-Welsh custom, she kept her maiden name her whole life. What we know of her is passed down to us in fragments in letters written between Goronwy Owen and his friends. The glimpses we capture paint a picture of her import in her son’s life. We know that she was well-educated, at least as far as was common in those remote days. She could read and write well, and she was a strict instructor in educating her son in his letters, his early habits of diction, and in his grammar.

More than this though, she was his most ardent supporter and defender. She was his sole source of love and tenderness in a world that very early, showed Goronwy its cold, hard edge.

His father was named, according to the old Welsh style, Owen ap Goronw; i.e. Owen, son of Goronw. In this we have a bit of our poets’ genealogy; he was named after his grandfather.

Like Goronwy’s mother, the little knowledge we have of his father is captured only in fragments snatched from letters. The information they reveal is not kind to the man’s memory, but it’s probably truthful. All sources are universal on their opinion and character of the man, and so we must pass him forward as he comes down to us.

First, Owen was a renowned drunk. This tidbit is especially revealing in that it comes to us from a time, place, and a people who adored their malt and their rye almost as much as they loved their children. That his abuse of drink was recorded at all is an indication that he really abused his drink. But this is not all. Owen was an abusive man, paying respect to no one, on no account at all. He abused his son, and on more than one occasion Sain Parri was seen putting her small body between the big man and the little boy.

In those days the only bards in Wales were “tavern bards”. The great Eisteddfod’s of old were fast asleep, not to be roused again for another century. The hero warriors of Wales were all but forgotten; dust in their graves, littered about the countryside, their stones un-deciphered and their treasures un-suspected.

In those days the only bards in Wales were “tavern bards”. The great Eisteddfod’s of old were fast asleep, not to be roused again for another century. The hero warriors of Wales were all but forgotten; dust in their graves, littered about the countryside, their stones un-deciphered and their treasures un-suspected.

The only place that a poet could find an ear willing to bend to the lilt of a rhyming meter was inside the tavern, with a pint of grog in his right hand and another drunk bard hanging on his left. The bards congregated in taverns, and there they whiled away the wee hours weaving rhymes and puns of witty rejoinders that thread by thread, kept the flickering flame of the Welsh language from being snuffed out.

Owen Goronw made a regular performance of his talents in just such a way. He was reported to be a skilled tavern bard who entertained the tavern crowd while entertaining himself. He may have been an abusive drunk who barely pretended to support his family, but it’s certain that he gave his son the gift of poetry – even if he did it contemptuously and accidentally.

The Morris Family

No mention of Goronwy Owen can begin without the introduction of the Morris family. Shortly before Goronwy Owen’s birth, Richard Morris (Morys ap Richard Morys) and his wife Margaret Owen (Margaret ab Morys Owen of Bodafon y Glyn), a family of noble Welsh lineage and substantial income, moved into the neighborhood of Penrhos Llugwy. They took up residence in the premiere house in the parish; Pentref Eiriannell, establishing themselves as the ranking family in the community. There they reared and educated their children. Most notable to our story are the three sons; William, Richard, and Lewis Morris.

Some sources claim that Sain Parri, Goronwy Owen’s mother, was related to the Morrises. Others state that she was a maid servant in the household. It’s possible that she was both, or neither. What is certain is that the Morris family “discovered” Goronwy Owen when he was very young, and they took him under their collective wing.

Lewis Morris (1700 – 1765) – This portrait was captured when Lewis was in his early-40’s.

Lewis Morris was born on March 2, 1700. He would have been in his twenties by the time young Goronwy Owen came to his attention. Given the gap between them in age, it’s unlikely that their early relationship was that of boyhood companions (as some have suggested.) By his twenties Lewis Morris was already an accomplished; some would say brilliant young man, well on his way to fame and greatness. It seems that the young Goronwy in some way distinguished himself to Lewis and the rest of the family. It’s likely that the distinction was born in the heart of Lewis’ mother, Margaret.

Decades after Goronwy Owen left Anglesy, upon learning of Margaret Owen’s death, Goronwy wrote an elegy to her memory that her sons cherished and that Welsh scholars place amongst his finest poetical work. In his letters to the brothers, he mourns Margaret’s loss as a son would. His exile from her was sharply felt by the poet, and her permanent loss was a blow. But I’m getting ahead of our story.

If Margaret was Goronwy Owen’s first “sponsor” in the Morris family, it was likely due to her pity and empathy for the boy. He dressed in rags. He was thin and always hungry. It was well-known that his father harassed him interminably, and that his mother, through her labors outside of their home was the sole support for the family. And yet, the boy was bright, energetic, humble, and grateful for any small attention paid him.

Our principal biographer, Rev. Robert Jones recounts the following:

“…he became an especial favorite of Mrs. Morris, who gave him bread-and-butter, with honey and treacle on it, and, when he left; presented him with a penny for pocket-money, paper for his school exercises, and some good advice seasoned with the pleasant prediction, ‘that he would one day make a fine fellow of a parson.’ Grateful for the kindness, he… turned round and said, “If I were a little dog, O how I would wag my tail!’”

Education

When Goronwy Owen was a small boy he attended one of Griffith Jones’ circulating schools in the nearby hamlet of Llan Algo. There he excelled most impressively, and was encouraged by his masters to continue his studies. Unfortunately Sain Parri’s household was extremely poor and while she did what she could to encourage and support her intelligent son, she was limited in her ability to send him forward.

It’s at this point in Goronwy Owen’s life that his friends become sponsors and patrons. Against Owen Goronw’s wishes, and in spite of violent outbursts against sending the boy away to school, Goronwy Owen is advanced to the Grammar School at Bangor in 1737 (across the Manai Strait, on the mainland.) There he learns his Latin and Greek, his classics, his mathematics, and his catechisms. Bangor is a renowned institution established in 1553 to serve the gentry and wealthy merchant classes of Anglesey and Gwynedd. Under the careful instruction of the schools’ headmaster, Edward Bennet and his assistant Humphrey Jones, Goronwy Owen becomes a true “classical scholar”.

He excels at school. He drinks it up like a thirsty man in a desert. He becomes a sponge for liquid knowledge and flowing contemplation. He was pronounced a prodigy at this early stage in his career. He had not quite yet earned the title of genius.

At Bangor, Goronwy is introduced, for the first time in his life (excepting the Morrises), to a better class of people than he’d ever known before. He develops friends and social contacts who show him opportunities and ambitions he could not have previously dreamed of. His imagination flowers and for the first time, he begins to see a future in these occupations which busy his mind day and night.

Lewis Morris takes the boy under his personal instruction during these years. He teaches him the complex rules of Welsh poetry. He gives him his first real books. He pushes him, and he is surprised – pleasantly surprised – at what the boy pushes back at him. In these early years the two become verbal and literary sparring partners, each one daring the other to greater skill and curiosity in how far they can go. A deep friendship and commitment develops that will last for decades.

Lewis Morris takes the boy under his personal instruction during these years. He teaches him the complex rules of Welsh poetry. He gives him his first real books. He pushes him, and he is surprised – pleasantly surprised – at what the boy pushes back at him. In these early years the two become verbal and literary sparring partners, each one daring the other to greater skill and curiosity in how far they can go. A deep friendship and commitment develops that will last for decades.

Unfortunately there is no sweet without the sour. About the time that Goronwy finishes his studies at Bangor in 1741, his mother Sain Parri dies. Letters passed between the Morris brothers (Lewis and William are still in Anglesey, Richard is in England) express their deep sadness at her loss, and their concern for Goronwy’s future without her solid foundation of moral support. Their concerns were not without merit.

Long Hard Path

Goronwy returns home from Bangor. He’s just eighteen years old. His mother is not yet cool in her grave and his father has already moved another woman into the house. Gorowy is lost. He’s broke. He has no skills except his poetry, his Latin, and the magic in his mind – but these things don’t put bread on the table or coin in his pocket. These are the first minor notes forming a repetitive chord that echoes throughout his life. At this stage though, Goronwy is still energetic and hopeful. He rallies himself and throws all his ambition into attempting to find something that will utilize his education, while paying his way in the world.

Pwllheli – In the late 19th century.

Goronwy applies and (probably with the assistance of Lewis or Richard Morris) is accepted to become one of the “Masters” at the Grammar School at Pwllhelli on the west coast of Wales, about 30 miles as the crow files from his home in Anglesey. The journey by sea or on foot (most likely) probably took several weeks to accomplish. He would have arrived hungry, haggard, and penniless, but we know that he did arrive and that he taught at the school for about three years between 1741 and 1744.

While he was there, I believe he met and befriended my two ancestors William and David Ellis Jones; two country boys from the hamlet of Dolgellau in Merioneth, about twenty miles from Pwllhelli (a world away as far as they were concerned.) The relationship that he formed with them must have been similar to the one that he had with Lewis Morris; one of mentor, tutor, and friend. I know he must have made a profound impression upon them that changed the course of these two young men’s lives; as well as the lives of their children and countless descendants.

That Goronwy Owen remained in contact with these two over the years of his life is without doubt in my mind. There exists no fixed record of it except in one single line in my family history that alludes to a greater fact, backed up by too many coincidences to ignore. But once again, I am side tracked.

Advanced Degree at Jesus College, Oxford

By 1744, when Goronwy was about twenty-one or twenty-two years old, the monotony of teaching propelled him to contemplate the benefits of an advanced degree in his education. Prior to going to Pwllheli he had attempted to gain a scholarship in order to attend Jesus College at Oxford. His initial efforts failed, but he obviously kept up his entreats while employed at the school. Perseverance paid off; by 1744 we find him at Oxford.

Curiously, some of his lighter biographers doubt the voracity of this fact. Apparently the records at Jesus College are not all they should be; as it appears by the record that he was accepted by the school but that he never actually attended except for a few days in 1742. A more careful examination of his history – specifically his correspondences between Lewis, William, and Richard Morris – show that between 1744 and the end of 1745 he was in full attendance at Jesus College, and that he was successfully ordained a minister in the Anglican Church. [3] More to the point, however, is that he was an employed Anglican minister for almost twenty years. The Church of England didn’t give orders to drop-outs. Advanced degree in religion was required for service.

Servitor at Oxford; 18th Century

It’s without question that Goronwy received a scholarship. He probably held a servitors [4] position while he attended to his studies. It’s also very likely that the Morris brothers, Lewis in particular, helped him with expenses and pocket money while he earned his credentials. With these credentials in hand, he put himself on the path of a career in the Anglican Church.

He could not have chosen a more difficult, less rewarding path, had he hand-forged an iron spade and then dug his own grave with it.

Career in “The Church”

The Church of England and its sister, The Church of Wales, was a powerful and very determined body politic. During the eighteenth century “The Church” was determined to wipe any evidence of Welsh culture; their customs, habits, and their language, off the face of the Earth. In Wales as in England, the Bishops were all Englishmen. The schools were all head-mastered by Englishmen. The services were all conducted in English. All records were kept in English. And every important appointment to every curacy and vicarage in the country was an act of political nepotism of the English bent.

In 1745, after much searching, Goronwy Owen was appointed to a curacy (parish pastor) in Llanfair, Anglesey – his hometown. He knew the vicar there and the position was in service to his old neighborhood; a community who knew and admired him for all he’d overcome and accomplished – and for the fact that he was their own.

The appointment took place when the Bishop of Bangor (who oversaw Anglesey) was out of the country. As soon as the Bishop (an Englishman) returned, he informed the local vicar that the curacy had already been promised to “a friend of a friend” and that the Welshman would have to vacate post-haste. This was a bitter blow. It was just one of many more blows that our poet would endure as his career in the Anglican community progressed.

With the ever-dependable assistance of the Morrises, Goronwy was finally appointed to a minor curacy at Ostwestry in Denbeighshire. The place was located on the western edge of England, near the Welsh border. Most of his parishioners were English or Welshmen who had thrown off their Welsh roots. He was an alien there and they considered him as such. He was made a master at the Grammar School where he taught Latin and Greek and the Catechism to his young scholars. But there were unfair difficulties; his master was a tight, mean, ignorant man who hated Welshmen and apparently Goronwy in particular. This was no place for a Welsh poet.

Despite his unhappiness at Ostwestry, he did manage to find a bride. Her name was Elin Hughs. She was of Welsh heritage, her father having been a moderately successful ironmonger and alderman, but she knew only a little of the language. They were married at Ostwestry in 1747 and seemed happy enough. But soon after their marriage Goronwy was determined to vacate the place for a better situation.

Uppington | Donnington

In 1748 he believed he had found just the one. The curacy at Uppington (frequently referred to as Donnington), also in Denbeighshire, became vacant. He applied for it and won it, but it was not all that he had hoped for.

First, the salary was tiny; just 26 pounds per year.

The neighborhood had its local dilemmas – most notably a sophomoric competition between the two local Squires. Squire “Boycott” and Squire “Lee” were constantly attempting to out “Squire” the other, with their competitiveness bleeding over into the local parish church. Most vexing to Goronwy was that they each attempted to win his loyalty by inviting him to elaborate dinners – on the same Sunday at the same time. They continually put him in a position of having to choose. To further complicate matters, Squire Boycott offered as part of the curacy package, a small plot of land for a garden and cow. As soon as it became apparent that Goronwy’s loyalty would not be divided to Boycott’s preference, Boycott withdrew the land, the cow and the garden, thereby depriving Owen’s small but growing family a substantial source of nourishment and comfort.

Goronwy’s small income proved a trial for the family, with little relief from the generally impoverished neighborhood. Despite his difficulties there were bright spots during his time at Donnington. Chief among them was the birth of his first child on New Year’s Day 1749[5], a son named Robert. In January or February 1750 another son, Goronwy came along. This period seems to have been an especially productive time for the linguist and poet as well.

We learn through letters he exchanged with the three Morris brothers that he has perfected his mastery of the Hebrew language. He asks the brothers to look for books for him in London, especially Arabic grammars. He’s eager to learn as much as he can of the “eastern” languages. His letters are filled with discussions of idiom, etymology, rules of grammar in Welsh and the dissection of compound words and corruptions in the language. They also overflow with despair at his distance from his friends, his isolation from everything Welsh, his incessant poverty, and his dislike of the English and their attitudes toward him.

In his communications, we see dark clouds starting to crowd into his once ebullient prose. Sarcasm replaces humor. Bitterness bites out from the pages and rips at the loose threads of his critics. Most notably, on March 25, 1752, he explodes in a tirade against Reverend D. Ellis, regarding a minor slight that Ellis felt Goronwy had made. The outrage which explodes from Goronwy’s pen demonstrates that it’s not just Ellis he’s outraged with. This screed has been building for a long time and he found his vent in a slim excuse. His verbiage is cutting, ruthless, and brutal. It illustrates the heart of an angry man who is clinging (barely) to shreds of threadbare pride. The verbal assault against poor Ellis is like that of a terrified animal striking out ferociously against a predator in a last desperate attempt to save its life. It’s so far beyond proportion as to be almost humorous, except what it reveals is too serious to make light of.

It’s clear that the cow-towing life of a Welsh cleric in an English world is getting the better of him. Poverty also; constantly having to beg assistance from friends to provide for his family is wearing him down. But the worst of all is seeing lesser men; lesser in his eyes in terms of their intelligence, accomplishment, and ability, find easy positions in localities he envies. His lack of progress is frustrating and humiliating. While Goronwy still maintains his outward humility, he knows that he is a genuine scholar. He believes this should be enough to send him into a position worthy of his skill and acumen. But inside the politics of the Anglican Church this will never happen; he is a Welshman. Still he hopes and tries – in vein.

It’s clear that the cow-towing life of a Welsh cleric in an English world is getting the better of him. Poverty also; constantly having to beg assistance from friends to provide for his family is wearing him down. But the worst of all is seeing lesser men; lesser in his eyes in terms of their intelligence, accomplishment, and ability, find easy positions in localities he envies. His lack of progress is frustrating and humiliating. While Goronwy still maintains his outward humility, he knows that he is a genuine scholar. He believes this should be enough to send him into a position worthy of his skill and acumen. But inside the politics of the Anglican Church this will never happen; he is a Welshman. Still he hopes and tries – in vein.

In early April of 1753, Goronwy learns at last that his friend, Mr. William Morris, has been able to assist him with a new appointment; and one with a substantial increase in salary to 35 pounds per annum. The place is Walton, very near the seaport of Liverpool in the west of England.

Goronwy Owen set off on foot from Donnington to his new situation at Walton (a journey of perhaps thirty miles), which was especially dangerous given the grave risk of highwaymen, gypsies and random thugs along the path. It most likely took him several weeks to complete. He left his wife and family behind without any real plan of how to move them. He also left his books; something as precious to him as his own children. Once again we find the Morrises coming to his aid. Within a few weeks the family – but not his books – joined him at Walton.

In the exchanges between the Morris brothers we see an ever-growing determination to get Goronwy back to Wales among friends. They try, but at every turn their attempts are thwarted by the anti-Welsh establishment of the Church.

Goronwy’s letters to Lewis and Richard of this period are filled with poetry and the criticism of the poor state of the Welsh language. He wants “some scholar” to create a really good Welsh Grammar. He complains that his books still have not come to him from Walton. He asks for the brothers to send him new books from England. He complains again about his poverty and isolation. His angst and misery have no outlet except through his letters. He has no friends nearby and no one to converse with in his native tongue.

And so, as anyone else in his situation might, he goes looking for an outlet.

A Second Life in the Taverns

A Second Life in the Taverns

Recall that the refuge of the Welsh bard was the tavern. It was a refuge his father knew well. And it was here, in the low streets of Liverpool, that Goronwy Owen found Welsh sailors and Welsh tavern bards who welcomed him and his effusion of rhyme and meter with open arms and with open taps.

The best of the bards had always come from the common class of Wales. The society itself was not so obsessed with rank (and rank upon rank) as the English. In the leveled rank of everyday folks, the bards emerged as they always had, and in the common tavern their arts flourished and were sustained – no matter how ardent the attempts to snuff it out by the Church, the Government, and the aspiring gentry who eschewed Welsh and sent their children to Exeter.

Goronwy Owen was, by this point in his life, openly acknowledged by his intellectual peers to be among the finest minds in Wales. His brilliance was known and credited, but still he lived in near abject poverty and constant debt. His career was relegated to the absolute backwaters of a kingdom that wholly disregarded him, and not even his closest friends could substantially remedy the situation.

We also have to understand that by this time the Morris brothers were all well-established in their own successful careers. Lewis, especially, had become a man of real status in England, and wealthy as a consequence. His reputation for excessive living was renowned, as was his reputation for engaging in endless legal battles regarding his various, lucrative business interests. Goronwy must have quietly chafed at the comparison. Lewis and he were intellectual equals in almost every respect. Except Lewis had every advantage of status and wealth, while Goronwy rotted in the wastelands. The only difference between them, as far as Goronwy could determine (and some scholars might agree), was the distinction of their birth. Had their situations been reversed, it might have been Lewis groveling for half a shilling to send a letter to his friend in London.

Lewis and Richard were deeply troubled by the reports they heard coming back from Liverpool. Drunken debauchery was nothing new to either of them and certainly nothing new to the period in Wales. But the rumors that began filtering in to Richard and Lewis contained more than drunkenness. More than the usual illicit exploits which were more common than not in that era. Lewis was no Puritan – his reputation as a glutton, a heavy drinker, and a flagrant womanizer were already widely renowned (almost to the point of celebration in the bawdy repartee between himself, his brothers, and their close circle of friends.)

Whatever it was that piqued their concern in regards to Goronwy’s behavior – it was more than just drink and women.

Maybe, as one biographer has suggested, William Morris is affronted by Goronwy’s tavern conduct because he personally intervened to secure the position at Waltion, and felt that Goronwy’s behavior reflected negatively on himself and the Morris family in general. This is certainly possible. However, the Morrises were not ardent Anglicans any more than they were Puritans. They were men of the Enlightenment who didn’t subscribe to the superstitions of most religious tenet. Had they been more dedicated to the Church of England they may have had more influence in securing a better situation for their friend.

This writer believes that whatever it was that brought on the censure from the Morris brothers is something more egregious than adultery or drunkenness. The letters exchanged between the four only whisper and allude. Nothing specific is spoken openly of. Just reproach and disapproval – condemnation. Something to do with Goronwy’s wife is mentioned (she’s taken to open drinking too.) The brothers are brutal in regard to her character. Meanwhile, in his response to these letters, Goronwy expounds on the fact that one of the greatest injustices the Welsh language has endured is that it has not been preserved and disseminated in print, as every other European language has. Is he intentionally ignoring the elephant in his small room? Or is he too humiliated to even defend himself?

Goronwy Owen has become a public drunk; a tavern lurker who seeks his companionship among the lowest of the low. They, apparently, are the only people who will provide his fragile self-image the approbation he so deeply craves. This is the world he occupies by darkness. In the light of day he writes letters to his friends exploding with poetry and prose the likes of which, scholars tell us, is as finessed and beautifully crafted as any other produced in the Welsh language. On Sunday’s he’s in the pulpit preaching morality and God’s equal justice and life everlasting, Amen. But he doesn’t believe it. He hasn’t experienced it. All he’s known since the death of his mother is humiliation, poverty, and disappointment.

He has other concerns too. His daughter Elin, who was born a few months after the family arrived at Walton, dies after a short illness on September 15, 1753. Her loss is devastating to Goronwy, who drowns his sorrows in elegy’s and ale. Compounding this, his sons are growing up without the Welsh language. Their accents are crude and as ugly as any in the worst parts of England. He feels he’s losing them to a society that will never appreciate them. He still learns regularly that much sought after promotions have gone to lesser men. One in particular, in Dolgellau, has been given to an Englishman. The loss of this one was especially painful, as it would have located him near close friends; his old students from Pwllheli William and David Ellis Jones, both now grown men. He grieves its loss but he tries to console himself in hyperbole;

“I was never so sanguine as to promise myself success, and therefore can have no disappointment.”

These are the words of a man resigned to failure. He’s breaking down to cliché where once there was energetic sarcasm and anger. The brothers Morris can’t help but see the rapid decline in the mental and physical condition of their friend. They conspire a solution to save their brilliant but ever more desperately spiraling poet-philosopher.

“…pregnant with mischief.”

The Temptations of London

In April 1755, Lewis Morris writes to Goronwy offering him an opportunity to come to London to establish a Welsh language church service sponsored and supported by the Honorable Society of Cymmrodorion – also the office of Secretary in that society in which his responsibilities would require the translation of various texts. The situation was perfect for Goronwy. It was work among people he loved and who appreciated his talents. Moreover, the Secretarial position at the Society rendered status (if not accompanying income) that could at least assuage his deflated self-image.

On the basis of this letter (which offered no promise or contract terms), full of hope and optimism, Goronwy resigns his position at Walton and proceeds on foot to London, once again leaving his family and his books behind. Both Lewis and Richard Morris were in town when he arrived some weeks later. How they received him, it is not known, but it must have been an apprehensive – if still joyful reunion. The first few weeks were no doubt spent introducing Gornwy to fellow Welshmen in London, and acquainting him with the various booksellers and places of interest in that cosmopolitan city; a city that Goronwy had never seen the likes of before in his life.

Lewis and Richard, and perhaps William too, chipped in to move Goronwy’s family from Walton to the metropolis. The family of four took up residence in a garret apartment on Bread Street Hill. Goronwy began to plan and work toward his new establishment.

Unfortunately, he also discovered the local taverns that were as common as mice in his neighborhood. His biographer, Robert Jones writes that his explorations in London “…were pregnant with mischief.”

History does not reveal to us what happened to this grand scheme on the part of the Morris brothers. What is known is that the Bishop denied the Cymmrodorion Society’s request for a curate, even though the Society was willing to fund it themselves. From there, the Secretarial position at the Society also fell through. It’s likely, though not recorded, that whatever trouble Goronwy created for himself in Liverpool, he brought the same habits with him to London.

It needs to be noted if it is not understood, that at least a plurality of Welshmen in London at the time would have been early adopters of the non-conformists sects. Whether Presbyterians or very early Methodists; they believed in a rigid morality; an adherence to temperance, and above all, a refraining from anything that smacked of the controversial. Goronwy Owen would have flown in the face of everything the main body of the Cymmrodorion Society believed was acceptable; regardless of what founders Lewis and Richard Morris thought of his brilliance.

Almost as soon as Goronwy Owen arrived in London, the three brothers begin conspiring to get him out of town. Whatever it is he has done (or is doing) it’s a serious complication to the brothers’ reputation, given their patronage and promotion. It’s unclear whether their hope to get him back to Wales is for Goronwy’s benefit, or for theirs. Given the disparity between their social and real conditions, it seems likely that Goronwy made himself an embarrassment to all who are associated with him. For what specific cause, we will probably forever be in the dark.

Further complicating matters between Goronwy and the Morrises is an issue of money and things. This problem seems trivial to our 21st century eyes, but in the era, it was a very real problem without an easy solution.

Debt and Disregard

Debt and Disregard

In order to finance his removal from Walton, Goronwy borrowed twelve pounds, placing his books and other cherished property as security against the debt. The books and other property remained with the lender at Walton while Goronwy moved on to London. The issue is that among the property was a particularly cherished and valuable antique Leathern Harp (an ancient and rare musical instrument), which had been lent to Goronwy ostensibly to teach his son Robert to play. The harp belonged to William Morris. Morris was incensed to learn that his property had been “hocked” and was now in the care of a stranger who had no sense of its antiquity, its value, or its proper care.

This marks the first serious breach between the Morris brothers and the genius poet.

In defense of Goronwy, we have to admit that it’s unlikely that he would have let his precious books get away from him. In William Morris’s defense, it was the principal of the thing. He considered it a grave demonstration of disrespect.

A Last Opportunity

Regardless of all this, the brothers were determined to find a situation for their friend. They did their work quickly and efficiently now that their own reputations were under observation. Lewis Morris, through his connections at the Temple (the legal courts in London) found an open curacy at Northolt, managed by a Dr. Nichols, who was Master of the Temple and also Vicar of Northolt. The salary was fifty pounds annually and the situation was located within twelve miles of London; far enough that Goronwy could be contained (hopefully), but near enough that they could keep their eye on him.

This new situation would have seemed ideal for any ordinary curate. The property offered a lovely, extensive garden which Goronwy aspired to manage, and it offered proximity to London in order to maintain his contact with the Welsh literati in town; those more supportive of him than some of the more puritanical dissenters among the Welsh in London.

Initially it seemed as if this plan would succeed. Goronwy found at least one friend at Northolt who spoke Welsh, a gardener who our poet nicknamed “Adam” in tribute to his talents. Together they planned a lovely garden and tended it together. It produced several moving lines of poetry from Goronwy’s pen, among them; “The poetry of earth is never dead.”

For a while Goronwy seems contented. He takes up fishing and writes poetry while reclining out of doors beside his trout stream. His garden grows and friends from London visit. His mood seems to be improving and he is writing as brilliantly as ever. It’s unfortunate that contentment was a stranger to Goronwy Owen. His only true companion for decades had been discomfort, isolation, and the gripping fear of failure. For the first time in his life he’s in a good situation, relatively near friends, and able to put food on the table for his children. The radical turn of circumstances left him unbalanced. In truth, Goronwy didn’t possess the tools to tend an abundant garden.

Half Moon Tavern, London

Shortly Goronwy made his way to London and to the Half Moon Tavern where the Cymmrodorion Society held its monthly meetings. In the tavern the usually reserved Goronwy Owen cast off the robes of the clergyman and revealed the dark tavern bard residing in his soul. He was the life of the party on more than one occasion. He was the centerpiece of conversation. And far too often he was too much for the Morris brothers to keep in check.

It’s unknown exactly what happened (there is an intimation that Elin is involved in some way) and exactly when it all came to a head, but sometime between late 1756 and early 1757, while Goronwy was still curate at Northolt, a fantastic breach occurred between Goronwy Owen and his friends and patrons. The results were catastrophic and permanent to Goronwy Owens career – as well as to his life – and unfortunately to the progress of the Welsh language and its literature.

Goronwy lost his curacy at Northolt and none other was put forth to replace it.

Broken Relationships and Broken Dreams

In May of 1757, in the last letter that we have from Goronwy’s pen to Richard Morris, we see him severing the relationship coolly, returning all of Richards books and manuscripts, and politely requesting that his manuscripts be returned to him. In what appears to be an almost childlike attempt at a peace offering to Richard, he includes in the box of books a pair of doves from his dove-house at Northolt. He offers these as a gift with his best regards.

In a twist of fate that is so in keeping with Goronwy’s entire life story, the delivery of the box is delayed significantly, and the birds inside expire. By the time the box reaches Richard, his books smell like carrion and are permanently marred with seepage from the decaying flesh of the rotting animals. Richard Morris is incensed. He obviously did not appreciate the attempt at peace-making. Goronwy Owen’s fate is sealed.

In their final conspiratorial act regarding Goronwy Owen’s career, the Morris brothers quietly petition friends to have him gotten out of England, out of Wales, and out of their way. For nearly twenty years they failed to help Goronwy gain a suitable position; one that would support his family and challenge his demanding brain. But now, almost instantly and inexplicably, Goronwy Owen is offered the Mastership of a brand new Grammar School at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. The job paid 200 pounds per annum – a fortune to an impoverished man like our poet. And topping it off, the offer came directly from the Bishop of London himself; Dr. Porteus, who was also the Chancellor of William and Mary in London.

Among other glowing recommendations and qualifications for this new role, Dr. Porteus described Goronwy Owen as “…the most finished writer of Latin since the days of the Roman Emperors.”

Goronwy knew the origin of the offer, and its intent. It was an offer he could not refuse.

William and Mary never had a Grammar School before this offer was dropped in Goronwy Owen’s lap. And the college, as impressive as it is today, was not, in that era, a destination spot for high intellectual pursuit. It was a school for making literate men out of rural planters sons; giving them the skills necessary to become successful men of agriculture and commerce. It’s clear to this author that the Lewis brothers moved heaven and earth, calling in considerable favors and sparing no expense, to get Goronwy Owen out of their way.

They succeeded. They may as well have had him hanged.

Exile

It’s a well-known fact that before America became the “Land of Opportunity” to millions of would-be immigrants, it was the dumping ground for all of England’s failures, criminals, and undesirables. Richard Hakluyt wrote, in 1584, in his long list of benefits of developing colonies abroad, that England could rid herself of unwanted persons and surplus population in the kingdom by “planting” them in the colonies. Hakluyt’s recommendation became English national policy, which was in full effect in 1757 with Goronwy Owen as its latest victim.

By December of 1757 the family things were packed, passage was booked, and the plan was sealed. In what appears to be a last minute twinge of guilt, Richard Morris steps forward and upgrades the family’s accommodations on board the vessel to the best class berth available. This, at least, would help make the voyage somewhat more tolerable, and possibly healthier.

By December of 1757 the family things were packed, passage was booked, and the plan was sealed. In what appears to be a last minute twinge of guilt, Richard Morris steps forward and upgrades the family’s accommodations on board the vessel to the best class berth available. This, at least, would help make the voyage somewhat more tolerable, and possibly healthier.

The Atlantic crossing was a notoriously risky undertaking. Weather always made the trip treacherous. Food generally spoiled before the end of the voyage. Fresh water went putrid or ran out completely. And due to over-crowded conditions, disease spread rapidly among passengers and crew. Few if any ships made the crossing without losing at least one, and usually many of its passengers.

This particular crossing was not unique. A large party of the ships passengers were convict women being sent into bonded service in the colonies. Before they even made it out of the Channel, these women began plying various illicit trades in service to the Captain and crew. Not long after, a serious infection spread among the ships passengers. Goronwy was impressed into service as both physician and pastor. Failing in the first occupation – for which he had no training – he succeeded in the second; consigning too many souls to heaven and their bodies to the depths.

Before they arrived in Virginia, Elin – who was pregnant at the time of their departure – was dead. (If this news reached the Morris’s, who had always reviled her, what was their reaction? Gladness? Regret? Nothing at all?) Goronwy Owen was cast into a new, completely alien country with two young sons to care for alone. He must have been absolutely desperate.

How he made it through those first few months is unknowable. It must have been incredibly difficult, both physically and emotionally. This man loved his country more than he loved his own life. He’d penned thousands of lines that regaled Wales majesty and beauty. Her mountains, her lush river valleys. Her rolling countryside and sweeping vistas – like the fantastic tidal flats beneath sheer cliffs on the east coast of Anglesey – near the small village where he had been born and grew into a young man. He’d been exiled from Wales for the better part of his life, but he never gave up her beauty and magic. He never stopped dreaming of returning.

That was before. When Goronwy Owen set foot on the sandy soil of Southside Virginia, everything he saw before him was flat and plain. It was a two dimensional landscape, horizontal and vertical, but with no depth; no dimension. It might has well have been a million miles from Anglesey, or all the way to the moon. He knew he’d never see Anglesey again. He knew he’d never hear the poetry of his language lilt from the lips of a truly gifted bard. It was over. The dream was done.

That was before. When Goronwy Owen set foot on the sandy soil of Southside Virginia, everything he saw before him was flat and plain. It was a two dimensional landscape, horizontal and vertical, but with no depth; no dimension. It might has well have been a million miles from Anglesey, or all the way to the moon. He knew he’d never see Anglesey again. He knew he’d never hear the poetry of his language lilt from the lips of a truly gifted bard. It was over. The dream was done.

Back in England, the Morrises wasted no time collecting their copies if Owen’s manuscripts – his beautiful poetry – and assembling them, editing them, sorting then, and preparing them for publication. The body of work was massive and the task took several years, but in 1763 the first edition of Y Diddanwych Teulauaidd was introduced. It was edited by Huw Jones of Langwm (a person whose talents and gift of comprehension, Goronwy Owen did not approve.) The introduction was written by Lewis Morris, but it is left unaccredited in this edition. Perhaps Lewis felt it a touch unseemly to be seen introducing and profiting from the work of a man he’d recently been so impatient to exile from the country.

It’s likely that Goronwy Owen never saw a copy of this book. Even less likely that he ever received a penny from its proceeds. It’s possible he never even knew the book existed until many years after it was published. What is known is that a second edition never came forth until long after Goronwy Owen’s death. Who knows, maybe he learned of the book and threatened to sue. (That’s a thought that makes one smile, especially given the legendary litigiousness of Lewis Morris.)

Virginia

This author would love nothing better than to finish this part of the story by informing my readers that Goronwy Owen turned over a new leaf upon his arrival in Virginia. It’s possible that he attempted to – but fate was never kind to this man – and fate was not done with him yet.

Owen was made Master of the Grammar School attached to the College of William and Mary on April 7, 1758. There he had the charge of an unknown number of scholars, most under the age of sixteen years. He taught Latin and Greek. At least one of his former students, a man named E. Owen, recalled him in a letter dated 1795, as “…a blunt, hasty-tempered Welshman, and esteemed a good Latin and Greek scholar.”

Within a year of arriving at William and Mary, Goronwy appears to have improved his circumstances considerably; most notably by marriage. Whatever his charms, he worked them successfully on a lady of substance, a widow, and sister to the President of the College, Mr. Thomas Dawson. History has unfortunately not left us with a record of her Christian name; she is only given to us as “Mrs. Clayton.” Her fate, once bound to Goronwy Owens, was almost doomed from the start. All we know of this period is that Goronwy seemed to stay out of trouble; a credit no doubt due to his accomplished and respectable wife. This moment of relative calm ends when “Mrs. Clayton” dies within a year of the marriage. They had no children together; that seems a fortunate turn, at least.

A year after her death Owen’s position within the cloistered community of the College has deteriorated to the point that he is dismissed on what appears to scholars more contemporary to his time than ours, as a trifling excuse that served as a “last straw” of sorts. The actual event that is alleged to have caused the resignation or dismissal was a drunken brawl between the young men of the town and the young men of the college; led at the helm by Goronwy Owen and another professor named Mr. Jacob Rowe. Both men were ousted from the College by August, 1760.

Mr. Rowe returned to England, to friends and family. Goronwy Owen had no refuge except his credentials and his ability to make excellent introductions for himself. (Would that he was as able of keeping his friends as he was of making them!)

As if fate and timing were not already cruel enough, it’s during this period that his youngest boy, Goronwy Jr., died. How his father took the loss, we can’t know. It’s certain that he was broken by it, at least for a time. But he still had Robert and for Robert – if nothing else – he soldiered on.

Brunswick County

St. Andrews, Brunswick County

Within a few months of his forced separation from William and Mary, Goronwy secured an appointment from Virginia Governor Francis Fauquier to the remote (and I do mean remote) parish church of St. Andrews in Brunswick County, Virginia. The distance of this parish from the Capital (then Williamsburg) was less than fifty miles south west as the crow flies. But in real distance and difficulty it was many times farther. Between the two locales lay a broad, very shallow, nearly unnavigable tidal sound, and many miles of completely unoccupied, thickly overgrown wilderness. In that era the only roads through this part of inland Virginia were rivers. Getting from Williamsburg to Brunswick County in 1760 using the most efficient means would have required boarding a vessel on the river at Williamsburg and sailing down to the port at Newport News or Hampton, then changing vessels and heading out into the Atlantic Ocean, turning south for fifty miles or so, then back in to a port at either Ocracoke or Portsmouth Island (a treacherous event, even today.) From there he would have had to board a barge which would carry him north and up to the Albemarle Sound, then up the mouth of the Roanoke River. The Meherrin River, a tributary of the Roanoke, would have taken him north and west to Brunswick County. This journey involves about two hundred miles of navigation around some of the most difficult shoals and reefs in the world. It’s known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic in tribute to the thousands of vessels and countless lives lost in this one narrow area of coastline. It’s not a trip anyone in that era would have taken lightly. It’s not a trip that skilled sailors take lightly today.

Barring a water passage, there were Indian footpaths through the forest. They were irregular, unmarked, informal highways used by hunters and trappers and a few straggling Indians who remained in the bush. Whichever route was selected, the trip would have been an undertaking almost as dangerous and certainly as uncomfortable as the Atlantic Crossing made by Goronwy Owen just two years previous.

Today this part of Southside Virginia still seems exquisitely remote. It has never, despite the passing of more than two-hundred and fifty years, had any serious industry operating in its vicinity besides agriculture. The people who are generationally native to this corner of the world still have the remnants of a peculiar accent and rhythm of speech, due to their general isolation from the rest of the state (and the world.) It wasn’t until the first paved roads were put through in the late 1930’s that the people of this region became exposed to the rest of Virginia and the larger community of America. Even today it retains much of the charm – and much of the backwardness – its isolation preserved for so many centuries.

In Owen’s time, this part of Virginia was an even more rural, sparsely populated woodland than the one I describe above. Its few residents were all farmers, and almost all of them engaged in growing tobacco for export to England and other parts of Europe. The trade that occurred (moving tobacco to market and goods back to farms) occurred via the rivers. The residents of Brunswick County made their preferred ports the one at Elizabeth City, North Carolina, or at Wilmington, NC – both being easier and safer to get to than the larger, busier ones in Virginia.

All of this geography and history is given as a means of emphasizing Goronwy Owens’ final and absolute exile from everything and everyone known to him. By coming to St. Andrews, he’d arrived, literally as much as figuratively, at the end of the road.

His life in that place must have been for him a maddening monotony of seclusion. If he felt isolated in Walton or Donnington, here he learned what real isolation was. His neighbors were not poets. They were not Welshmen. They were not learned men, not scholars. Most probably didn’t even bother to attend church regularly to hear his barely prepared sermons. Certainly among them he found some kind souls, but he never found a circle of indulgent, erudite friends like those he had and had lost in Wales and England. The people of rural Brunswick County were hard people, smart about the things that mattered to their survival; but they probably had little patience with a poet-philosopher wrapped up his own pathos. They were too busy building what would become agricultural empires, making some of their children and grandchildren among the wealthiest people in America. They were not scholars, but they were industrious as hell.

Tobacco Cultivation in Colonial Virginia

It’s entirely possible that their model provided just the kick in the pants that Goronwy Owen needed.

From his little Parish Church in St. Andrews, Goronwy Owen somehow managed to conspire some method of obtaining a small farm. Like his neighbors, he planted tobacco. Before long, he was married again. His third wife; Joan Simmons, gave him three children; Richard Brown Owen, Goronwy Owen (named after the lost son), and John Lloyd Owen.

In the ten years between his arrival in Virginia and 1767, no evidence of communication survives between Goronwy and his friends or relations either in England or Wales. It’s reasonably well-documented that among his former patrons, there were attempts to communicate with him – to get some word of how he was doing and his whereabouts. None of these attempts were successful as far as the records reveals. However, some communication between the bard and someone back home must have occurred, because in 1767 a letter from Goronwy arrives at the Navel Office in London addressed to Richard Morris.

Its contents, among general greetings, contain an Ode on the Death of Lewis Morris. Lewis died in April of 1765, and word somehow got to Goronwy. Ten years had elapsed since he repartee’d with his old friends, and yet this ode stands among the finest poetic work ever produced from the pen of Goronwy Owen. His skill and his talent had not dulled an iota, despite the time spent in exile from his native tongue and his literary sparring partners.

Richard Morris was moved. Terribly moved by the letter and the Ode. His response to Goronwy, the biographers tell us, is filled with genuine affection and sincere feeling for the loss of his old friend. His sorrow is profound and the depth of it is genuine. He attempts to heal the once deep breach between them and he regrets it ever occurring. His effusions of regret are lengthy and his evident sense of guilt and is unmistakable.

As fate would have it (cruel as she is) – Goronwy Owen is dead and in the ground by the time Richard’s letter reaches Virginia. No response was ever returned. There was nothing but silence. Dead silence for decades.

Robert Gets the Last Word

Thirty years later, in 1795, other attempts are made to locate the bard or his descendants. His son Robert was located, still living in Brunswick County. His response upon being asked for information about his father was, ‘…before I give the information, I must first know who will pay me for it.’

Robert Owen; born in England and dragged, along with boxes of books, from one poverty-stricken post on one end of England to the next. His sister lost to malnutrition or lack of medical care. Then the whole family cast across an ocean like convicts. His mother dead at sea with a baby in her belly. His little brother lost in the backwoods of a godforsaken country no rational person would chose to live in. His father all the time moaning about the brilliance of a language that no one but he can speak. And then the old sot dies when Robert is not yet twenty years old. Madness. Infernal madness! Of course he hates these people inquiring about his so-called famous father. If his father was so damned important, why didn’t they save him and the rest of his family from this interminable exile when they still could have? Bastards!

That’s probably about what ran through Robert Owen’s mind when the letter arrived. The last thought he had on the subject was likely, ‘They can all go to hell.’

It’s the last that England or Wales would have for more than a century on what became of Goronwy Owen. It was a fitting slap in the face to a nation that turned its back on its brightest son. Anything less would have been disingenuous.

Real Friends

How did Goronwy Owen learn of the death of Lewis Morris in April of 1765? Lewis was a wealthy and successful businessman, but by the time of his death he was in his retirement at his country home at Penbryn on the west coast of Wales. His celebrity in England was not so grand that his death much registered there. It certainly would not have made the newspapers in the colonies of America. Even if it did, it’s unlikely that the news would have made it as far as Brunswick County.

So how did Goronwy Owen hear of it?

His biographers tell us that there is no evidence of his correspondence with anyone in Wales or in England between 1760 and 1767. No physical evidence perhaps; but there is circumstantial evidence of correspondence between Wales and Virginia in those interim years, as well as evidence of continued association between Owen’s American born descendants and the children and grandchildren of Owen’s old friends in Wales.

The first matter of circumstantial evidence is simply that someone got the news about Lewis Morris’s death to Goronwy Owen within a few months of its occurrence.

The second matter of evidence is the existence of William Jones and his brother, David Ellis Jones. These two men were rural farm boys when they met Goronwy Owen at the Grammar school at Pwllheli. Their father was a barely literate yeoman farmer. But from the time of their departure from Pwllheli they were both dedicated scholars of Welsh, of Latin and Greek, and of Hebrew. William, who had been intended for the Church by his father – declined the opportunity [6] (despite the vast leap in social status it would have offered both his immediate and extended family.) It’s this author’s belief that William saw (and suffered with) the career of his friend – a brilliant man and gifted scholar – and determined that the life of a Welshman in the English Church was not the life he wanted for himself.

You have to understand how unusual it was for a son in that day to thwart his father’s plans for his career. Declining the opportunity to take orders – William’s fathers primary wish – was a brazen and rebellious act. And it was not at all in keeping with the sober character of the man we know William became. He was a good man, a good son, and an excellent father. But he could not, by his own account, take orders in the Church of England, and he didn’t. He became a printer and a non-conformist preacher, an ardent nationalist who spawned several generations of Radical Welshmen who carried the flame of their language forward – demanding respect and earning it every step of the way.

Our next matter of circumstantial evidence is the first book that we know William Jones of Bryntirion published; a Welsh-English dictionary – a book that Goronwy Owen lamented for decades was the single most wanted volume in all of Welsh lexicography. This book was probably not the book that Goronwy would have published had he ever been given the opportunity, but it was a start; a new beginning for the language. If nothing else it was homage to an old friend’s dream.

An even stronger association exists in one of the publications of William Jones of Bryntirion’s son, Lewis Evan Jones. His office printed the second edition of Y Diddanwch Teuluaidd in 1817, following the first edition (1763) produced by Lewis Morris and Huw Jones as soon as Goronwy Owen was out of the country. Lewis Evan Jones extended this successful book into a periodical, which ran for several years.

From here we have to look forward into the generations of descendants among both families.

Robert – the son who wanted payment from wealthy former friends of his father – he named his first son William Ellis. If this is an amazing coincidence, I’ll be the first to admit it. But to me the sentiment is not coincidental. He named his son after the best, truest friends (William and David Ellis Jones) he felt his father ever had. The coincidence does not end here. Other sons were named Lewis and Richard, creating a pattern of repetitive first-naming that persists in the same generations among the children of William and David Ellis Jones.

The evidence grows even stronger on down the line.

Franklin Lewis Owen, fifth grandson of the bard, settled in Mobile Alabama, where he held offices of the Federal Government, among them, collector of the port. He reared a large family there and was well-respected and established. One of his sons served in the confederate Army upon the outbreak of the Civil War.

Rather inexplicably – and coincidentally – Richard Evan Jones, son Lewis Evan Jones, grandson of William Ellis Jones of Bryntirion, immigrated to America and settled in Mobile, Alabama (almost 500 miles away from his closest cousins in Virginia.) In Mobile he became active in civic concerns, an established pillar in the community, and was – like Franklin Lewis Owen’s son – a Confederate War soldier and veteran. The two men had to have known one another as friends and neighbors. The idea that Richard Evan Jones chose to locate himself in Mobile, Alabama (rather than Richmond, for example, where he had known family relations) is absolutely insupportable to me, except that he had equally dear friends in Mobile willing and able to help him. Those friends, I put forward, are the descendants of Goronwy Owen.

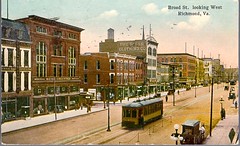

My final and most compelling piece of circumstantial evidence is the immigration to America of Thomas Norcliffe Jones, son of David Ellis Jones (Goronwy’ Owens’ student at Pwllheli), and brother to the renowned bard and scholar William Ellis Jones (Gwilym Cawrdaf), in the period just following the War of 1812. As far as the records show, Thomas Norcliffe Jones had no friends and no family in Virginia. Richmond was not a destination point for Welsh immigrants of the period. There was no evidence of any Welsh community in Richmond; unlike other parts of the country; Utica New York and Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, as example. Nevertheless, to Richmond he went, and there he and his family prospered.

I believe that Thomas did have friends in Richmond. I believe that the sons and grandsons of Goronwy Owen were established in Richmond before Thomas Norcliffe Jones arrived, and that they assisted him and helped him and his son William assimilate into the close-knit community of Richmond’s old, colonial era families. There is almost no other way to explain William Ellis Jones (1838 – 1910), son of Thomas Norcliffe Jones, instant entrance into the closed clique of Virginia Society, or his rapid rise into the social elite of that town. Had he been just the unconnected son of a brand new Welsh immigrant, this ascent would not have been possible.

I’ll take it one step further and state that I believe that the reason my ancestor, William Ellis Jones (1838 1910), the confederate soldier and historian/publisher of Richmond, converted to the Episcopal Church in opposition to his father’s Presbyterian loyalties was as a direct result of the influence of the Goronwy Owen connection. Goronwy Owen’s descendants would have remained in the Established Church of England as long as their father lived. Once the American Revolution was concluded, the Episcopal Church, still tied in principal to the Church of England, became the house of worship and indeed the center of society for the best classes among all Virginia’s citizens. William would have naturally wanted to affiliate himself with this established clan.

Goronwy Owen was a vociferous letter writer. His mind over-flowed with verbiage, ideas, and observation that needed an outlet. When his exile was complete and his ties with the Morris brothers were severed, does it seem reasonable that he just silenced his brain and put down his pen? It’s impossible. He continued his correspondences with those old friends who were willing and happy to hear from him. I doubt seriously that the Jones Brothers in Dolgellau were his only pen-pal companions. I don’t doubt that the letters have not survived. The Jones of Dolgellau were not the “great men” of England whose letters were considered valuable historical artifacts before the ink was dry on their pages.

These men, William and David Ellis were not wealthy. They were not men of prestige and fortune like Lewis Morris, or his brothers William and Richard. They were, however, loyal forever friends.

Goronwy’s isolation in Brunswick County Virginia may have been a nearly unbearable exile to the genius poet. But that exile, I am convinced, was made endurable by frequent and regular contact from his beloved home country and friends who genuinely cared about him and his family. They cared to the degree that lasting relations developed between children and grandchildren, across thousands of miles. What an impression this man must have made on two small boys back at Pwllheli, that such a bond across time and distance could last? Goronwy Owen must have been one remarkable fellow.

We know that already. Lewis Morris, his “great man” friend, turned conspirator in the plan for his permanent exile, stated, “Goronwy Owen was the greatest genius of this age that ever appeared in our country.”

It’s unfortunate that his country and his “friends” could not tolerate the genius on their own soil. Virginia may not have recognized Goronwy Owen’s genius, but at least we offered him some semblance of solace and a final place to rest his wearied bones.

Owen’s Legacy in Virginia

Virginia is a state with a rich and proud heritage. It has produced generations of both professional and armchair genealogists and historians, as well as more than its fair share of authors, poets, and public servants. The state’s courthouses and parish churches offer a veritable treasure trove of documentation in regards to the its earliest occupants and their progress through the centuries. Dr. Robert Jones wrote in his 1901 biography of Goronwy Owen of his inability to discover “…any account of his home, his parish, or his new life partner….”

It’s clear that Dr. Jones failed to make his way across the Atlantic, as the records still remaining in Virginia, as well as Goronwy Owen’s many descendants, provide us a wealth of details that he clearly did not try terribly hard to locate.

From the vestry books we have an exchange of letters between the parish at St. Andrews and Governor Fauquier, regarding Goronwy Owen’s recommendation to the parish, his trial period, his final appointment as the rector on September 14, 1760, as well as terms of his pay (in tobacco, not coin.)

The courts of Brunswick County record on May 27, 1765 that Goronwy was charged and found guilty of public drunkenness and use of profanity. He was fined fifty pounds of tobacco, with proceeds of the sale going to the poor of the parish.

By July, 1769, Goronwy Owen was dead. The Parish Vestry books include a note stating the Church’s intent to pursue Owen’s executors for overpayment of his wages.

On the 26th of March, 1770, Goronwy Owen’s will was presented to the court. The executors named by Goronwy Owen; William and Beverly Brown (probably relatives of his wife Joan), refuse to serve as executors and ask the court to name a replacement. The very brief will is recorded in the records of the courts, and the inventory of Owen’s “personal estate” is interesting and revealing.

As to the disposition of his property, he leaves his land in life trust to his wife, to be divided equally upon her death among his four sons; Robert Owen, Richard Brown Owen, Goronwy Owen, and John Lloyd Owen. He leaves – curiously – the disposition of his “personal estate”, i.e. his personal effects; his things, to the discretion of his executors. The list of things that Gorowny left is unremarkable given all we know about him. That he left the disposition of these things to the discretion of his executors is remarkable in my opinion. I cannot explain it.

The first few items in the list of effects were four slaves; Old Peg, Young Peg, Bob, and Stephen. Of all Owen’s “possessions” these four individuals were of the greatest financial value at 97 pounds, 10 shillings. How the court disposed of them, isn’t at hand.

Other effects included furniture, paintings, a looking glass, a mirror, etc. The inventory includes livestock, tools, dishes, and various cabinets, boxes, and tables. The list of items that is most interesting to me is the inventory of Owen’s books. His library was extensive and it’s clear that the vast majority of his books came with him from England. There are twenty-five or so individual titles listed, and then a single entry indicating “A parcel of old authors, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Welch and French, in number, 150.” The entire collection was estimated to be valued at 3 pounds. (Oh! To possess a time machine!)

There is one item, or rather a collection of things, not listed in this careful inventory; a collection of papers, written material, manuscripts – anything produced from Goronwy Owen’s pen. He certainly wrote while he was in Virginia. We know he was working on a Welsh Grammar when he left England. That would have been an incalculably important manuscript had it found its way back to Wales.

What happened to Goronwy Owen’s papers? I would love to believe that they are still around somewhere, carefully boxed and preserved, patiently waiting in some ancient Virginia library for rediscovery. (Things like this do occur occasionally.) Or perhaps they were sent home to relatives in Wales and made their way into some wonderful private library in a great old house. It’s not incomprehensible; the idea that his papers survived. Stranger things have happened. But then again, it’s just as likely that these Virginia scribblings were discarded as soon as Goronwy was dead.

Goronwy Owen’s gravesite is reported to be in Brunswick County. There is a modern stone on the property that makes the claim. There’s a very nice plaque to his memory (placed by the Cymmrodorion Society, in 1969) at the College of William and Mary, Swem Library. I’ve see reports that the ruins of his house still remain standing in Brunswick County. While I have not visited it myself yet (I plan to make that trip in the autumn of 2013), I have seen photographs and I have my doubts. The building shown in the photographs is clearly a 19th century structure – no earlier. Perhaps later.

Descendants

The real legacy that Goronwy Owen left in Virginia was his children, some of whom grew up and married and had children of their own. They spread from Brunswick County, settling in Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, and probably many more places across this vast country. Today his American descendants probably number in the many hundreds, living from one end of the continent to the other. Most probably have no idea they are related to this obscure Welsh genius, poet, and scholar. I wonder how many among them got his gift for languages, his scholarly bent, or his infatuation with complex, metered, rhyme? Some certainly did. These gifts don’t pass quietly out of the genetic mix, as I well know.

Remembrance

In closing it seems fitting to offer up a bit of poetry. This one is not from our bards’ pen, but instead in homage to him. It is from Lewis Morris; great-grandson of the Lewis Morris from this history. This elegy first appeared in the Transactions of the Honorable Cymmrodorion Society, in its first issue, more than one hundred years after the death of Goronwy Owen. I’ll leave you with it:

Friend, dead and gone so long!

Was it not well with thee, while yet thy tread

Gladdened this much-loved land of thine and ours?

Came not thy footsteps sometimes through life’s flowers?

Knew’est thou no crown but that which bears the thorn?

Amid the careless crowd, obscure, forlorn;

Who sittest now among the blessed dead

Crowned with immortal song?

A humble peasant boy,

Reared amid penury through youth’s fair years,

The fugitive joys of youth thou didst despise,

Ease, sport, the kindling glance of maiden’s eyes;

Thou knew’st no other longing but desire,

With the young lips parching with the sacred fire,

To drink deep draughts of knowledge, mixed with tears —

A dear-bought innocent joy.

—————-

Sources:

The Poetical Works of the Rev. Goronwy Owen (Goronwy Ddu o Fon) with His Life and Correspondence, Vol. II, Edited by Rev. Robert Jones, BA, Vicar of All Saints Rotherhithf (1876) London | Longmans, Green & Co.

The Poetical Works of the Rev. Goronwy Owen (Goronwy Ddu o Fon) with His Life and Correspondence, Vol. II, Edited by Rev. Robert Jones, BA, Vicar of All Saints Rotherhithf (1876) London | Longmans, Green & Co.

Goronwy Owen, William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 3, January 1901, pp. 152 – 164

Goronwy Owen, William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 9, No. 3, January 1901, pp. 152 – 164

Lewis Morris: The Fat Man of Cardiganshire, By Gerhaint H. Jenkins (2002) Ceredigion | Journal of the Ceredigion Historical Society Vol. 14, no. 2, p. 1-23

Lewis Morris: The Fat Man of Cardiganshire, By Gerhaint H. Jenkins (2002) Ceredigion | Journal of the Ceredigion Historical Society Vol. 14, no. 2, p. 1-23

Footnotes:

[1] The old Julian calendar, which was superseded by our current one, the Gregorian calendar, was not completely adopted across Britain until (as late as) the 19th century in some places. According to the contemporary calendar, Goronwy Owen’s birth fell on the 13th of January 1723.

[2] March 12, 1700 according to the old calendar.

[3] Letter from Goronwy Owen to Richard Morris, dated June 22, 1752.

[4] “Servitor” is a scholarship day student who earns his keep by “waiting on” the paying pupils.

[5] Robert Owen’s birth fell on the 13th of January 1749, according to the modern calendar.

[6] The Origin and History of Methodism in Wales and the Borders, by David Young (1893) Edinburgh | Morrison & Gibb, Printers, See: Pages 589 – 590

Notes:

In the special collections department at Swem Library, at the College of William and Mary, there is one very interesting artifact worth noting. It is – if authentic – the only item in the Goronwy Owen Collection at that library that is actually associated with the man, from his period. It is:

Item 1999.084: Miniature Purported to be of Goronwy Owen, circa 1800s (Ed. Note: If authentic, date is incorrect. It would have to be earlier. He died in 1769)