Thoughts from the other side of the wall….

Tag Archives: Richmond

The Delight of Research Never Ends!

From The Spirits of Bad Men Made Perfect project… never-ending research is bliss to me.

Reading Between the Lines – Civil War Diary

For months now I have been parsing through William Ellis Jones, II’s Civil War diary, plucking details, context, and hidden subtext from his scribbles. While the diary has been previously used by many Civil War scholars and is quoted in a countless list of books and articles about the 1862 Peninsular and Shenandoah marches and battles, no one to date had done a comprehensive study of the whole text.

For months now I have been parsing through William Ellis Jones, II’s Civil War diary, plucking details, context, and hidden subtext from his scribbles. While the diary has been previously used by many Civil War scholars and is quoted in a countless list of books and articles about the 1862 Peninsular and Shenandoah marches and battles, no one to date had done a comprehensive study of the whole text.

Despite my lack of academic pedigree or publishing chops, I have the advantage over most of those scholars in that I’ve spent eight years studying William Ellis Jones, II’s family history. Having those details – knowing who, where, and what he came from – has given me a really precise lens through which to examine the intent and implications of the diary’s author.

That lens has allowed me to pluck meaning from seemingly benign statements. For instance; in August of 1862, William and his battery witness the advance of the whole of Jackson’s Army marching brigade after brigade into the Shenandoah Valley. He describes the endless lines of soldiers as “stretched out to the crack of doom.” This statement appears on its face to be a simple description of a very large, ominous looking advance of troops, until you dig deeper and discover why William chose to enclose the description in quotes.

“…stretched out to the crack of doom.” is a quote taken from the speech of a Mr. Stanton, published in the “Proceedings of the General Anti-slavery Convention” from the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, published in London in 1841. (Page 479.)

Mr. Stanton used the phrase in reference to the United States’ desire to extend and legalize institutionalized slavery not only within her own borders, but to use the nation’s growing international strength and influence to extend industrialized slavery into Mexico, Latin America, South America, and beyond. Today the idea that such an expansion of slavery was ever conceived seems preposterous to us, but a study of the antebellum, pro-slavery coalition operating inside and on the periphery of the United States Congress prior to the Civil War shows us that this kind of international expansion of slavery was exactly what the proto-Confederates intended. This was to become a central component of the United States foreign policy; if southerners could manage to wrest a majority in the House and Senate.

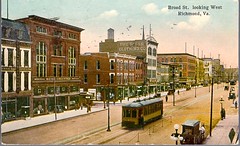

The idea that William read this speech, was familiar enough with it to quote from it, and had a firm conceptual grasp of the idea that the massive army he was watching (and serving in) represented a real physical manifestation of the policy that Mr. Stanton warned against in 1841, is simply amazing to me. He was just twenty-four years old, and had been born and reared in a city (Richmond, Virginia), whose very foundations were laid by the hands of slaves.

William in no way celebrated the idea of slavery in the use of this quote. Rather, I believe, he carefully selected it to record his true feelings about what was happening, while remaining just ambiguous enough for self-preservation (should his diary fall into the hands of one of his commanders.)

The diary is dotted with examples like this one; statements that show us the veiled concerns and conflicted loyalties of a less than enthusiastic confederate soldier.

When viewed from this perspective, it becomes clear why William chose to never write or publish any of his own words about the War, and why he chose to rear his sons with social and political leanings that were anything but in keeping with the spirit of glorification of the “Lost Cause”.

More to come.

Taking It to the Next Level – Crowd-funding my Book

Over the last year (more), I’ve studied my Civil War and related history books and performed countless hours of online research. All this has led me to some truly amazing places; discoveries about my family’s past that I could not have imagined in ten lifetimes of imaginings. It’s been great – to say the very least.

That said, there are just some things that can’t be found through Google. I need to “go to the source” in order to get at some details that professional historians haven’t yet ferreted out or seen fit to publish. I’ll provide a few examples of what I mean:

The original manuscript of William Ellis Jones’s Civil War Diary is in Ann Arbor Michigan. I need to sit down with the original, compare it against the transcription my grandfather copied into The Baby Book, and note any errors or corrections into my own transcription for my book. In addition, I’d like to photograph the document if the library will allow that.

– Cost of that trip is going to be around $1800.00

I need to spend at least a few days at The Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, Virginia, going through their archives and learning what I can about William Ellis Jones, his business, his associations, etc.

– That trip is going to cost around $500.00

I need to spend at least two days in Richmond researching property records and wills, to determine why William Ellis Jones, III was left essentially penniless, even though his grandfather was a successful man who owned a good deal of property. (I want to prove or disprove that his uncles stole his inheritance.)

– That trip is going to cost around $500.00

I need to take several weeks (broken up over the course of several months), visiting the Civil War Battlefields that are relevant to William Ellis Jones’s 1862 march. In addition, I need to see Gettysburg, which I believe is the last battle William fought in, before Spotsylvania. And of course, I need to visit Spotsylvania, where William was wounded in 1864, effectively ending his career as a Confederate soldier.

– These trips will cost around $300.00 each (some more, some less, totaling around $3000.00)

What I would LOVE to do (although I doubt I will get the opportunity) is go to Caernarvon, Wales and do some research on Thomas Norcliffe Jones, the father of William Ellis Jones, in order to add some flavor to the section of the book that deals with William’s upbringing, his father’s devoted Welsh Wesleyan roots, and the Welsh Jones clan dynasty of authors, poets, and book publishers.

– By my best estimate, that’s a $8000.00 trip abroad.

Last but not least, I need to join the North Carolina Writer’s Network so I can get the final draft of this thing in front of some critical readers, as well as possibly luck into an interested publisher at one of the workshops or conferences (not to mention benefit immensely from the company and insight gained from co-mingling with other writers.)

– Joining fee is $75.00

– Annual Conference is $350.00 – $500.00 (depending upon where it is.)

– Workshops $75.00

– Travel for all of the above events will set me back $400.00 – $500.00

That’s quite a Christmas list. Since I stopped believing in Santa a long time ago, and since $8.00 per hour, 12 hours a week, isn’t going to get me there either – I’m taking this thing to the streets.

I am going to put together a proposal for GoFundMe.com, and start soliciting money for this project – just the same way my ancestors solicited subscribers prior to publishing a book of poetry or sermons or political rantings about ironmongers in South Wales. If people can raise thousands of dollars for pee-wee football teams or cheer leading or bone marrow transplants or breast implants, I can raise at least a few bucks to get this book printed.

I’ll let my fair readers know once I get my prop up on GoFundMe.com.

I’m building a Facebook profile and Page for this project too. (Don’t start… I know…)

I look forward to your support.

You must be logged in to post a comment.